Hazel McCallion sprained her ankle helping Mississauga residents during the train derailment of 1979 while leading the city

Published January 30, 2023 at 5:04 pm

Every new political leader will, at some point, face their first crisis. And their response to it will be telling.

As far as crises go, the one that rose up before rookie Mississauga Mayor Hazel McCallion just four minutes before midnight on Saturday, Nov. 10, 1979 was a real doozy–a showstopper that truly stopped an entire city in its tracks as its nearly 300,000 residents, most of whom were asleep or getting there quickly, tried to wrap their minds around what had caused the dark Mississauga sky to be lit up just moments earlier like never before.

And never again since.

For McCallion, who was 58 at the time and just a year or so into what would become a 36-year reign as mayor of Mississauga, her first major test had arrived.

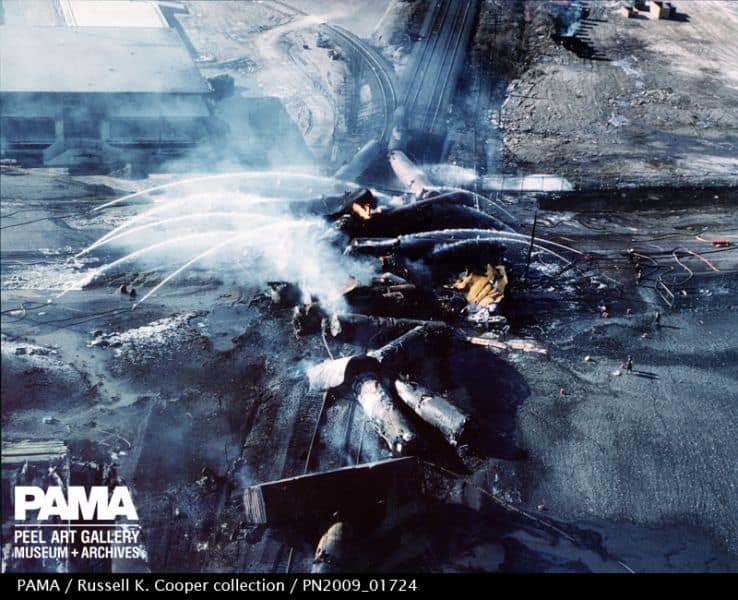

A huge explosion at the Mavis Rd. rail crossing just north of Dundas St. W. sent the resulting orange fireball about 1,000 feet into the midnight sky.

The time was 11:56 p.m. and the growing city of Mississauga was about to be forever changed, thrust into the national and international spotlight as the unfolding crisis would make headlines everywhere.

Three minutes earlier, as a 106-car Toronto-bound train carrying 90 tonnes of chlorine and tankers full of other highly flammable materials including propane and butane sped by the Burnhamthorpe Rd. crossing, a red-hot set of train wheels fell off and flew 50 feet through the air.

The train wheels landed in the backyard of a Freeport Cr. resident.

Moments later, train cars began crashing into one another and 25 of them left the tracks.

The subsequent explosion was sudden, and deafening. It rocked numerous neighbourhoods in the immediate vicinity. And it awakened tens of thousands of Mississauga residents who had already gone to bed. Scores of others, meanwhile, were already at their windows, on their balconies and at the bottom of their driveways eyeballing the massive fireball and trying to figure out what had blown up.

Hazel McCallion and others talk to the media. International media attention focused on Mississauga, the first time that many around the world had heard of the city.

At 11:57 p.m., every available piece of firefighting equipment in Mississauga, including dozens of fire trucks, was sent to the scene of the explosion and crippled train.

As people across the city were still trying to figure out exactly what had happened and what was ablaze, and just how serious the situation was, a second explosion–considerably more powerful than the first–rocked the city at 12:01 a.m. as Saturday gave way to Sunday.

The flash of light was seen by people as far away as Niagara Falls, Oshawa and Peterborough

“The noise awakens tens of thousands throughout Toronto. The blast was so powerful that one tanker is hurled a kilometre away,” Heritage Mississauga writes in its account of the historic event. “Firefighters do their best, but can make no impression on the raging flames. Eleven of the derailed tankers contain highly-explosive propane, and one tanker held the 90 tons of chlorine.”

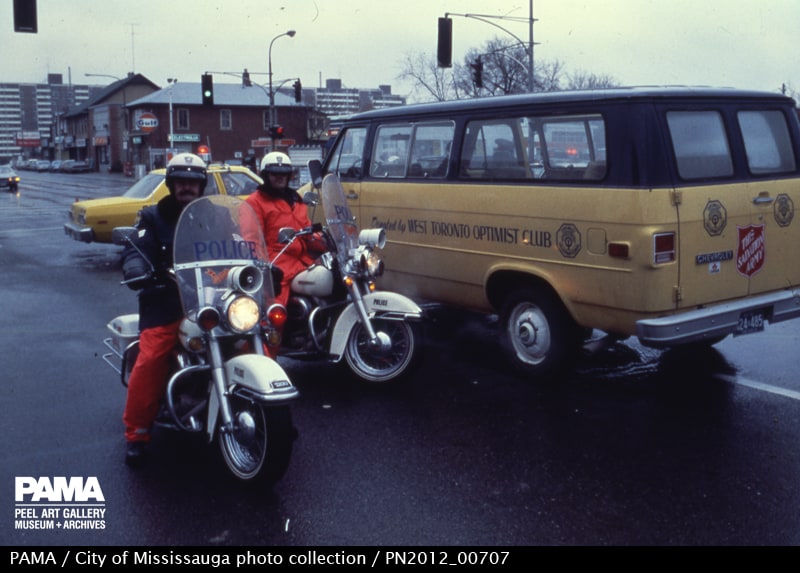

In stages over the next several hours and day, the vast majority of Mississauga residents were evacuated from their homes, many kept from returning for nearly a week.

In all, more than 200,000 of the city’s 294,000 residents at the time were forced to leave their homes in what was, at the time, the largest peacetime evacuation in North American history.

And there at the helm, calmly speaking before the TV cameras and to throngs of reporters to deliver regular updates on the ever-changing and dangerous situation, was McCallion.

She cemented her hard-working reputation by continuing to deliver updates even after spraining her ankle while helping evacuate some residents from their homes. McCallion hobbled to press briefings despite her injury.

By the vast majority of accounts, Mississauga’s fledgling mayor had met the moment head-on in November 1979 and in the ensuing four-plus decades, her handling of the significant crisis was often cited as a demonstration of her competence.

Heritage Mississauga offers a full and detailed account of the entire ordeal, from the time the train left its starting point in Ohio earlier on Nov. 10, 1979 to nearly a week later when all residents finally returned to their homes to resume their lives.

Seen here is a photograph taken by Toronto Telegram news photographer Russell Cooper, who was given special permission to fly above the explosion site.

More than 200,000 people were ordered out of their homes and businesses, the largest peace time evacuation until New Orleans braced for Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Sherway Gardens, Square One (pictured above), Peel Memorial Hospital, Queensway General Hospital, Sheridan College Brampton and Oakville, the International Centre, and various schools served as evacuation centres to house the displaced. (Looking at Square One in this photo, you’ll notice how relatively flat the western City Centre skyline is.)

There were no deaths, and Mississauga and Peel’s response is still seen as a model for emergency response.

A planning room filled with representatives of various agencies.

The Mississauga train derailment changed the city–and other municipalities–in several ways, including making it a priority for the city to have a detailed, up-to-date emergency plan in place should disasters strike.

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising