How Hamilton might find way out of our housing deprivation crisis

Published March 17, 2023 at 6:04 pm

A housing policy expert who spoke to Hamilton leaders recently said the response — remember CERB? — to the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic might have shown a way out of the crisis.

Hamilton, which by all empirical evidence, is aiming to create a new housing secretariat that will provide a road map out of the shortage. That will be presented to Mayor Andrea Horwath and city council next month. Ahead of that, council had a special general issues committee meeting last week where Steve Pomeroy, a senior research fellow at Carleton University who also heads Focus Consulting Inc., offered pro tips on how Hamilton might tackle the problem. Jim Dunn, a McMaster University professor who will be helping chart the housing roadmap, also spoke.

“There is no way you are going to build your way out of this,” said Pomeroy, who has advised in the not-for-profit housing sector for three decades. That seemed to tie in one of his more intriguing suggestions — that rental assistance might be more pennywise than building supportive housing (which costs around $450,000 per unit).

“Instead of focusing on bricks-and-mortar buildings, perhaps focus on people’s ability to pay,” Pomeroy said. “The accidental experiment we saw in 2020 proves this can be very very effective… Most folks who are unfortunate enough to end up receiving social assistance want to get off. It is the same thing with affordable housing. So what you can do is take an approach of ‘let’s help you.’

“For instance, in San Diego (California), they started an achievement academy. They pay rent at 30 per cent of the minimum wage but assist people with getting there by helping them improve labour market skills and financial literacy. A little bit of that goes a long way. And increased rent payments generate revenue for the city.”

That accidental experiment was the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit, which the federal government temporarily created three years ago to benefit employed and self-employed Canadians whose means of support were directly harmed by COVID-19. Pomeroy said an unintended consequence was that many Canadians who got CERB felt less angst about paying for core needs. He added that the federal 2021 Census, conducted the following year, contained a one-off “statistical aberration” when it came to Canadians’ views of affordability.

“It would not show up if we did it right now,” Pomeroy said. “But that income assistance had a massive effect on actually reducing core needs. So we should be thinking of introducing rental assistance.”

Hamilton, and other single-tier Ontario municipalities, apply to senior levels of government (Ontario and Canada) for supportive housing projects. Ontario is one of very few provinces, states or territories in Canada and the U.S. where cities build supportive housing. That Dunn and Pomeroy were facilitating discussion during the week of the 25th anniversary of former premier Mike Harris downloading social services to municipalities did not go unremarked upon.

That legislation was passed on March 7, 1998.

“The municipal downloading was one of the things that motivated me to run for city council,” said Horwath, who was the Ward 2 councillor from 1997 to 2004. “And here we are and we’re back here.”

The point of the meeting seemed to be about moving councillors into a shared headspace about short-term and long-term solutions.

“We want to set up an action plan that will have some quick wins before November,” healthy and safe communities general manager Angela Burden said, referring to the start of the 2023-24 budget process.

The council in Hamilton has members from all three parties that have been in government and/or the official opposition in the last quarter-century. Horwath was first elected as an Ontario New Democrat MPP in 2004. As leader, she led them to opposition status in the 2018 and ’22 provincial elections before resigning to run for mayor. (Hamilton Centre MPP-elect Sarah Jama held the seat for the ONDP in the March 16 byelection.)

Ward 9 Coun. Brad Clark was a cabinet minister alongside former premiers Harris and Ernie Eves with the Ontario PC Party, which is now in power. Ward 15 Coun. Ted McMeekin held four cabinet portfolios — including municipal affairs and housing, as well as community and social services — in the Ontario Liberal governments of premiers Dalton McGuinty and Kathleen Wynne.

“I think Hazel McCallion said it best,” McMeekin said at the special GIC meeting, alluding to the longtime Mississauga mayor who died in February at age 101. “In Ontario, it’s the federal government that has all the money, the provincial who has all the power, and the municipalities who have all the problems (to fix).”

The presentation by Pomeroy also gave a layered critique to Hamilton’s housing-first approach. Pomeroy said Hamilton is one of the few Canadian cities earnestly trying to solve chronic housing deprivation. But the results are mixed.

The city’s Housing and Homelessness Dashboard shows that 1,545 people in Hamilton lack housing — exactly thrice the shelter bed capacity. For every person whom the city and partnered community agencies are able to help find a place to live, one person “inflows” into the shelter system.

“Hamilton is one of the leading communities in trying to end homelessness, but you’re not getting anywhere,” Pomeroy said. “If we want to end it, we have to end flows into it.”

Analyst: ’Can’t build your way out of it’

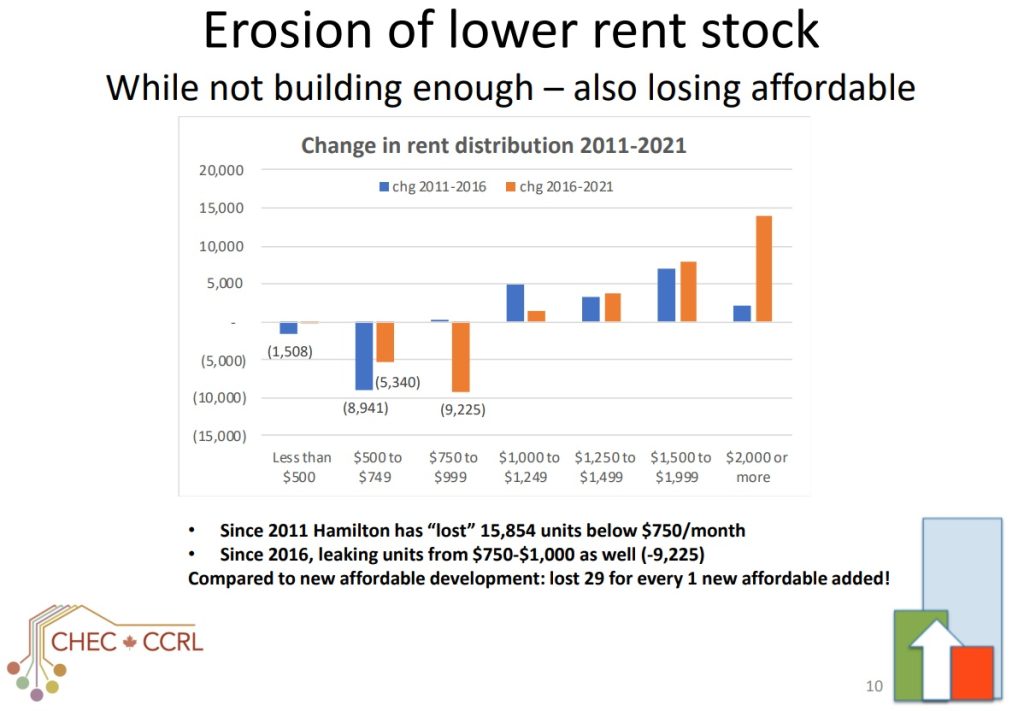

A separate report also estimates that an individual in Hamilton needs a $65,000 annual income to afford a one-bedroom rental. Pomeroy also presented findings that the Hamilton metro area, when Burlington and Grimsby are included, lost nearly 16,000 units that rent for under $750 a month. That is considered affordable for a household income of $30,000 a year.

“You can’t build your way out of it,” Pomeroy said. “If those units for under $750 aren’t around anymore, where are they supposed to go? That’s where the housing-first programs fall apart.”

Another chart showed Hamilton lags behind Peel Region (Mississauga and Brampton) and Peel Region in securing funds from the federal Liberals’ $80-billion National Housing Strategy. Pomeroy explained that most of the federal money in “unilateral funds” that can support long-range planning. Only 15 per cent is for specific projects, which is what Hamilton has traditionally pursued.

“Other places have put together a strong business case,” Pomeroy said. “They’re coming to Ottawa (the seat of the federal government) saying, ‘We want portfolio funding,’ instead of pitching one-by-one and hoping to get lucky.”

Hamilton has also had a back-and-forth with the Ontario government about provincial housing targets, the new Bill 23, and the highly contentious Greenbelt land swap. The province, last fall, also rejected the city’s choice in 2021 to freeze its urban boundary.

Several cities and municipalities say they do not buy that Bill 23 (The More Homes Built Faster Act) is going to alleviate housing shortages.

“I would contest that just building new supply isn’t going to address the affordability problem,” he said.

Aging population also on horizon

Council voted 16-0 to receive the report. Dunn also advised councillors of a coming demographic shift. In 2026, the first wave of baby boomers (Canadians born between 1946 and ’64) will turn 80. That generation made it into an age in a period of higher birth rates than Generation X (1965-80 births) and millennials (1981-96). (Some Canadians in their 40s who straddle the latter two generations identify as Xennials.)

“There are currently 350,000 people around the Greater Golden Horseshoe area over the age of 80,” Dunn said. “They are mostly suburban, and car-dependent. But that age group will go up to 1.05 million in 20 years.

“Where are they going to live when they can no longer drive? How can they receive home healthcare over that kind of scale? Cities will need to look more at housing options around transit-oriented communities, so they can have more independence and not be stuck in their houses. That’s a big-picture planning issue.”

Approving new builds does not mean the for-profit building and development firms will step to it. One analysis published since Hamilton’s meeting shows 29 major Ontario municipalities reached only 41.1 per cent of their combined housing target in 2021. Hamilton, at 54.6 per cent, ranked seventh.

And that should say *2022* completions. Still writing the wrong date on my Excel tables. Corrected version.

And I also accidentally had New Tecumseth in place of Newmarket. New Tecumseth built slightly more homes. pic.twitter.com/5QGQ5v9GlH

— Dr. Mike P. Moffatt 🇨🇦🏅🏅 (@MikePMoffatt) March 15, 2023

The stated aim of Bill 23 is to add a net 1.5 million new homes in Southern Ontario. But a report prepared for The Alliance for a Livable Ontario by planner Kevin Eby shows more than 2 million units were already approved by local governments at the end of 2019.

Hamilton had approved around 110,000 builds, including 87,600 within its erstwhile urban boundary. The province wants it to build 47,000, and it also ordered the urban boundary expanded last November so development could take place on ‘whitebelt‘ lands.

(That term is for farmland within the City of Hamilton that is not the provincially protected Greenbelt.)

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising