WATCH: The first film Ivan Reitman made at McMaster in Hamilton in 1968; ‘Animal House’ and ‘Ghostbusters’ filmmaker has died at 75

Published February 14, 2022 at 3:53 am

Ivan Reitman was known to correct people who believed “National Lampoon’s Animal House,” the greatest campus comedy ever made, was based on life in the residences at McMaster University in Hamilton.

However, Reitman’s comedy chops and grand ambition were evident when he was a student at Mac in late-1960s Hamilton. He also attended Oakwood Collegiate in Toronto.

The “Animal House” producer and “Ghostbusters” director made his first student film in Hamilton in 1968, and it’s available on YouTube. At that time, the young Reitman was part of the McMaster Film Board, a student-run society where “SCTV” and “Schitt’s Creek” star Eugene Levy and film executive Daniel Goldberg also got their starts.

Reitman, who was catalytic in the growth of the Canadian film industry and also conquered Hollywood, died at age 75 last Saturday (Feb. 12) at his Montecito, Calif., home. The filmmaker is survived by his spouse, Geneviève Robert, and their children Jason Reitman, Catherine Reitman and Caroline Reitman. His two eldest children are also directors.

Thanks to a YouTube channel called Famous First Films, Ivan Reitman’s debut student film is free to view.

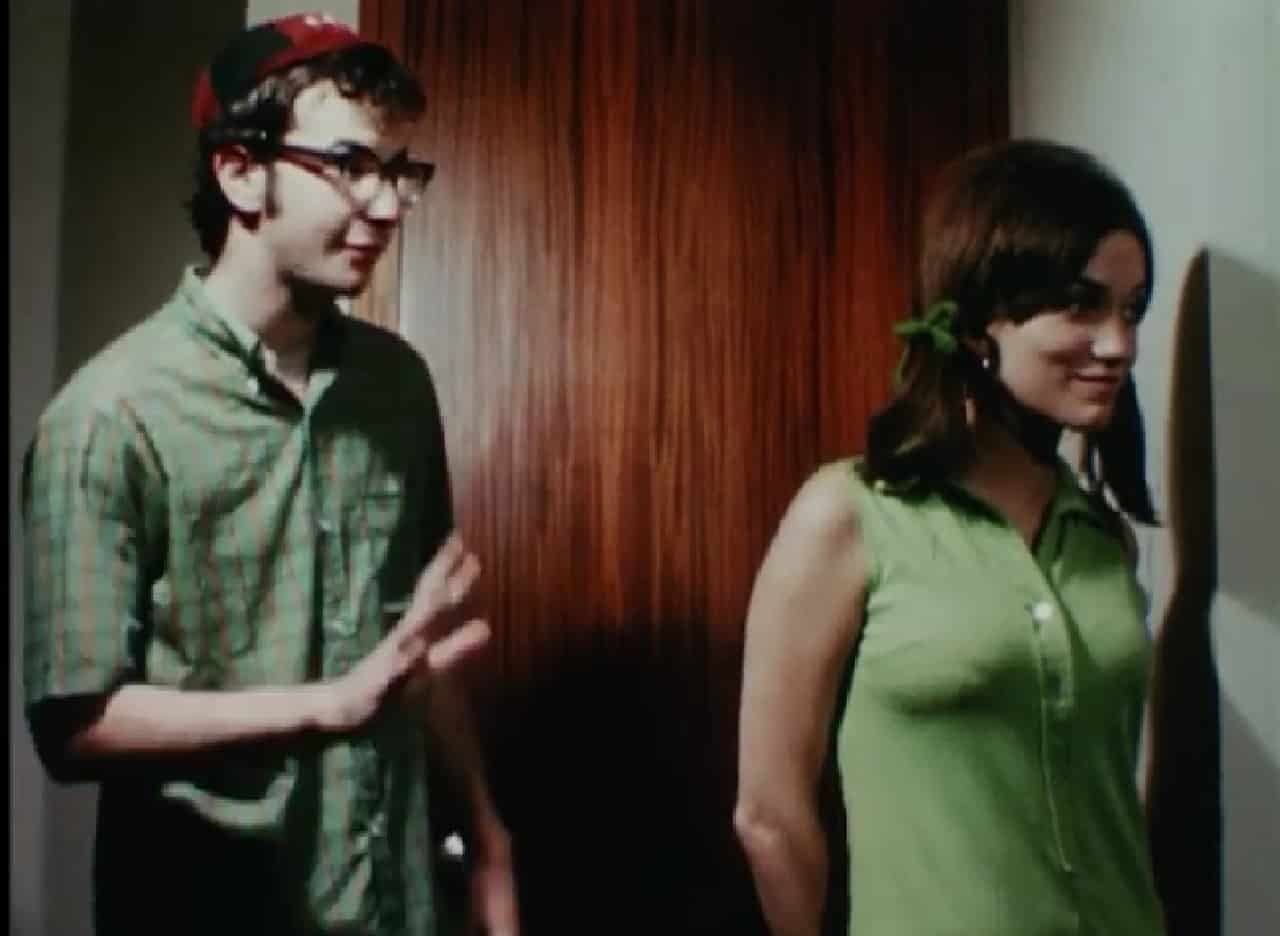

Entitled “Orientation,” the 22-minute short satirized materials that were often presented to first-year students. Along with directing, producing and writing it, Reitman also handled cinematography and music.

The story follows a Mac frosh named Dan — played by the aforementioned Goldberg — as he navigates his first days on campus. (Spoiler alert: Dan gets the girl, portrayed by Lyn Logan, but not without falling into the water at Cootes Paradise.)

The short aired on Canadian TV and was also picked by 20th Century Fox. Watching it in 2022, one can appreciate that the 22-year-old behind the lens would go on to help performers and directors such as Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, Chevy Chase, David Cronenberg, Christopher Guest, Rick Moranis, Bill Murray and Harold Ramis find success and stardom.

And some of the scenes and shots Reitman created in “Orientation” are very similar to those that appeared a decade later in “Animal House,” when the degens from Delta Tau Chi took down Dean Wormer and the snobs from Omega House at fictional Faber College.

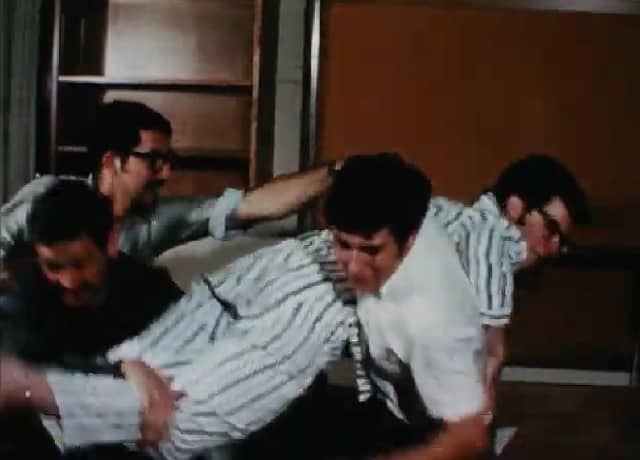

For instance, four minutes into “Orientation,” a pyjama-clad Dan is pulled out of his bed by three older male students in some form of hazing ritual. They carry him outside and load him into their Chevy.

In “Animal House,” Delta pledges and Kent Dorfman and Larry Kroger get pulled out of their residence-room beds in the middle of the night to get sworn into Delta. Seniors Donald (Boon) Schoenstein and Eric (Otter) Stratton use fire extinguishers to awaken the pledges.

Kent and Larry end up receiving their Delta Tau Chi names from sergeant-at-arms Bluto Blutarsky (“Why Pinto?” “Why not?!”) and dancing drunkenly to “Louie Louie” with their new frat brothers.

There are worse ways to spend a weeknight in your first month at school.

Just ask Reitman’s protagonist in “Orientation.” Dan’s tormentors dump him kilometres from campus in the dead of night, decades before handheld devices with GPS. He ends up walking home, barefoot, arriving back at Mac at the break of dawn.

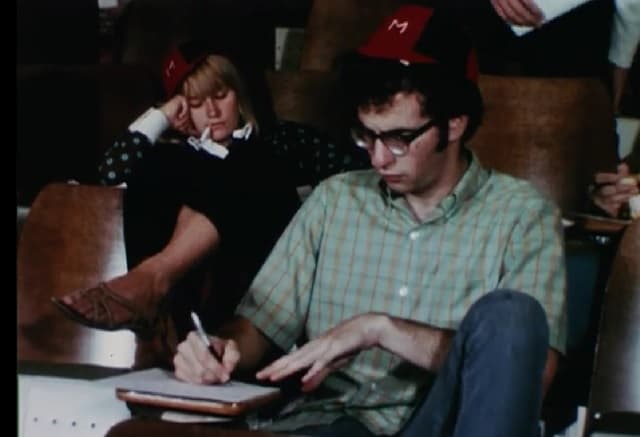

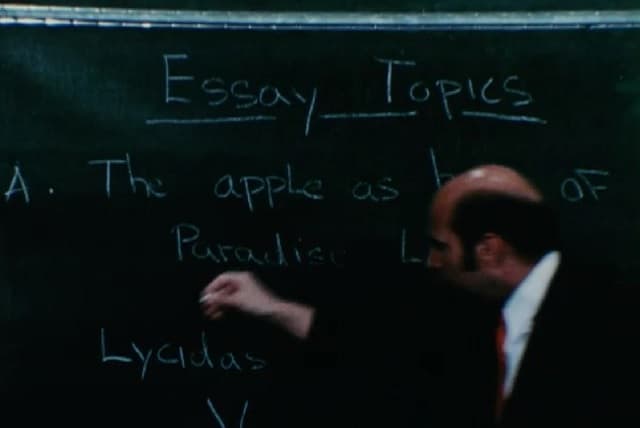

A few minutes in movie time later, Dan attends an English class. Most of the students are wearing maroon-and-black Mac beanies. The phrasing ‘zoning out’ might not have been in the lexicon 54 years ago, but it would have been apt here.

The students are straining to hang in with a lecture on John Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” that bane of generations of literature students. To quote another professor, at another Ontario university, circa some time in the late 1990s, “If you are ever experiencing insomnia, I recommend reading ‘Paradise Lost.’ I found it worked admirably.”

Coincidentally, that same 17th-century epic poem also makes an appearance in “Animal House,” when Kent and Larry — since renamed Flounder and Pinto — attend English class.

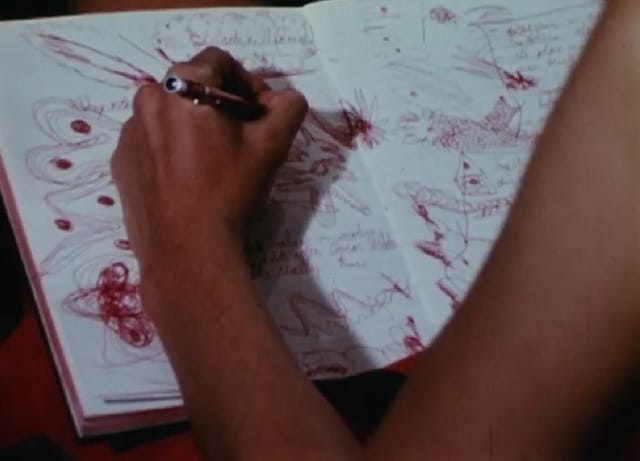

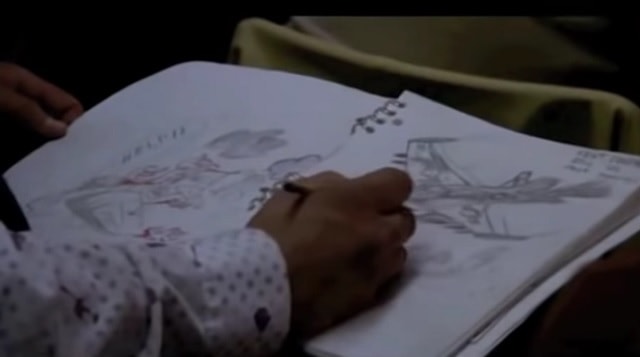

Reitman’s scene from 1968 includes an over-the-shoulder shot that catches a female student creating an elaborate red-ink doodle in her notebook instead of taking notes. The same gag is repeated in “Animal House,” with Flounder drawing a Second World War aerial battle instead of paying attention to his professor.

The professor in “Orientation” seems oblivious to fact that the centuries-old epic poem is giving his students the thousand-yard stare. In “Animal House,” Faber professor Dave Jennings realizes he’s losing the room and candidly shares his distaste for “Paradise Lost,” and his sympathy for the long-suffering Mrs. Milton.

While Reitman’s fingerprints are on the scene, Sutherland’s monologue about Milton and plea for students to pass in their coursework (“I’m not joking — this is my job!”) was written by co-writer Douglas Kenney. Kenney also had a bit part in the film as a Delta frat brother called Stork, who leads the Faber marching band down a dead-end alley during the homecoming parade.

‘A real mix’

For the record, the fictional Faber College in “Animal House” was not a stand-in for any particular school.

Reitman’s networking with the “Lampoon” certaintly planted a seed for it to be made. In the early 1970s, he approached the magazine about branching into movies. That led to his involvement with “Lampoon” forays into a syndicated radio show and an off-Broadway stage show.

The drive to make “Animal House” picked up after Lorne Michaels hired away several “Lampoon” performers and writers in 1975 for the first season of “Saturday Night Live.”

Reitman told The Canadian Press in 2013 that the script derived from “a real mix” of the experiences that he and the film’s co-writers — Kenney, Ramis, and Chris Miller — had during their school days. Kenney and Miller were Ivy Leaguers from Harvard and Dartmouth, while Ramis was a graduate of Washington University in St. Louis.

Once Universal Studios picked up the script, they deemed Reitman too inexperienced to direct. John Landis was hired instead.

Reitman’s first feature film as a director ended up being 1979’s “Meatballs,” which was also Bill Murray’s first starring role. The modest summer camp comedy became the highest-grossing Canadian film of all time in the U.S. and Canada.

Unique chapter at Mac

The McMaster Film Board is also a unique and forgotten chapter in Canadian film history. The MFB was founded in 1966 by John Hofsess, a Hamilton native. At a time when the Hays Code still existed in the U.S. film industry, Hofsess was influenced by avant-garde, boundary-pushing performers such as Andy Warhol and the pop group The Velvet Underground.

One of Hofsess’s movies led to he and Reitman, the cinematographer and co-producer, facing an obscenity charge. They beat the rap when the film was found not to have violated community standards.

As “Orientation” and his later works might show, Reitman’s comedy tastes ran more to the broad and audience-friendly.

All told, he directed 18 films between 1968 and 2014. Those included “Draft Day,” “No Strings Attached,” “Stripes” and “Twins.” He was also a producer on 2009’s “Up In The Air,” which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

His final producing credit was on 2021’s “Ghostbusters: Afterlife,” which was written and directed by his son, Jason.

Ivan Reitman was born the year after the end of the Second World War, to Hungarian Jewish parents on Oct. 27, 1946 in Komarno, Czechoslovakia. His mother Klara was survivor of the Nazis’ Auschwitz concentration camp and his father, Ladislav “Leslie” Reitman, had been an underground resistance fighter during the war.

The family came to Canada as refugees in 1950, when Ivan was four years old, and settled in Toronto.

Reitman received the Order of Canada in 2009.

— with files from The Canadian Press

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising