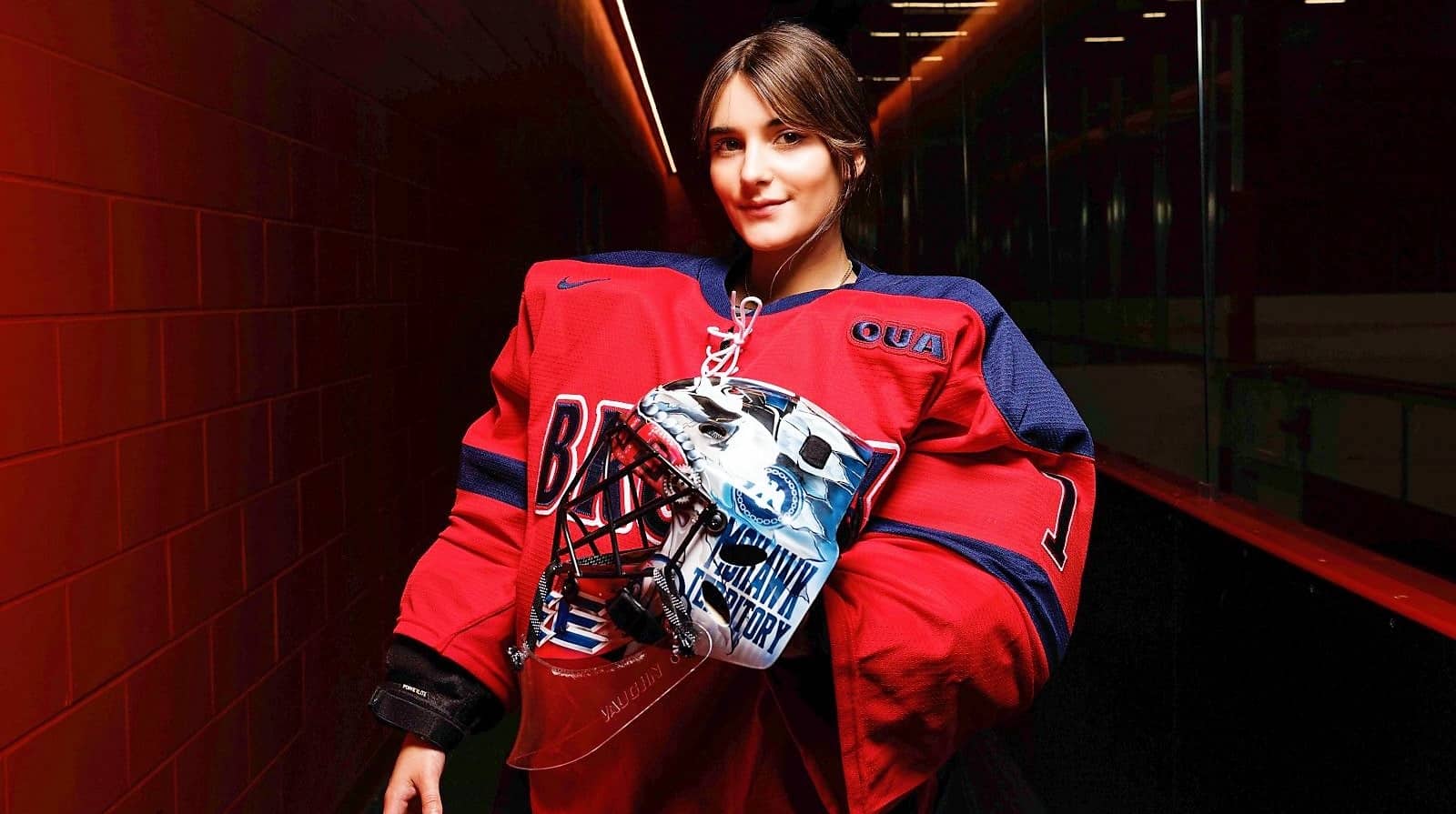

St. Catharines’ university goalie honours Indigenous ancestry on her helmet

Published October 3, 2022 at 3:34 pm

You could say the goalie for the Brock Badgers’ women’s hockey team wears her heritage in her heart, on her sleeve… and yes, on her goalie mask.

The second-year Psychology student, whose family’s heritage has ties to the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, had her goaltender mask repainted with a mix of meaningful imagery that is close to her heart.

“My back plate (which holds the helmet in place) is a red dress hanging in a stall to represent Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls,” she said.

“The rest of the helmet is portraying a traditional Indigenous headdress. I also have my community on the side with the words Mohawk Territory.”

Also written on her mask is the name of Maela Sharon Holmes, an 11-year-old goalie from St. Catharines who passed away suddenly on June 22. The young hockey player was taught by Hollowell in goalie training programs.

While the helmet often reminds Hollowell to reflect on the history of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, she wants to encourage others to do the same.

She was deeply involved in the campus’ National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30. where the university hosted a series of events remembering the more than 150,000 Indigenous children forced away from their families and into the residential school system, where many suffered various forms of abuse.

“This day is special to me because it’s an opportunity for the country to honour the memory of all the children we lost and found, and those who still haven’t been found in unmarked graves at residential schools across Canada,” said Hollowell last week.

More than 4,100 people are documented as having died in the residential school system while the sites of unmarked graves hold the remains of more than 1,900 unaccounted for individuals, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

“Reflecting on what this day means to every Canadian comes down to awareness and education, not blame,” Hollowell said. “It’s about acknowledging the past, learning from it and never repeating it in the future. It’s important to understand that we need action, not just words. Actions can be small yet have a huge impact.”

Hollowell’s great grandmother, June Jean Powless, was a survivor of the residential school system.

“I never had the chance to meet her, but she’s a big reason why I am outspoken about Indigenous issues and why they are near and dear to my heart,” Hollowell said. “Listening to my mom, she said that my great grandmother never recovered from her time in residential schools.”

Intergenerational trauma needs to be addressed and actioned to walk the path of recovery, said Hollowell.

“The sins committed in residential schools not only negatively impacted the children, but also their families and subsequent families,” she said. “We need to understand intergenerational trauma and start healing and recovering as a country.”

Hollowell said wearing orange on National Day for Truth and Reconciliation — also known as Orange Shirt Day — is a small gesture that carries a big message to raise awareness of the impacts of residential schools.

“Having an Indigenous perspective in sports, especially with women in hockey, is such an honour and has given me opportunities to connect with so many individuals,” Hollowell said. “I hope others use this day to take the time to learn about a culture that once faced being erased.”

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising