Research from Hamilton’s McMaster University reveals failure to protect Canadian landscapes could massively accelerate climate change

Published November 12, 2021 at 12:47 pm

Canada could be sitting on a melting pot of carbon catastrophe, according to a study led by World Wildlife Canada (WWF-Canada).

McMaster University researchers in Hamilton were part of the study that determined how much carbon is actually stored in Canada’s landscapes — amounting to 405 billion tonnes. The research suggests that as global temperatures rise and that land decomposes or is disturbed by human intervention, that carbon could then be released into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change.

The total amount of carbon mapped by the researchers is the equivalent of about 30 years of human-caused global greenhouse gas emissions (at 2019 emission levels).

Alemu Gonsamo, assistant professor at McMaster’s Remote Sensing Laboratory, explained how these carbon stores are key to helping hold the global average warming temperature to 1.5°C during a panel presentation at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland.

“[The] national carbon map will have a huge impact on the way conservation activities and policies are approached to prioritize nature-based climate solutions,” says Gonsamo.

The findings are the first-ever comprehensive analysis of its kind and show that 95 per cent of carbon in Canada is found in the top one metre of soil. 24 per cent of that is found in peatlands. The rest of Canada’s carbon is found in trees, other plants, dead plant material and roots.

“Tens of thousands of field measurements were fed into a machine-learning algorithm to train satellite observations, including space-based laser scanning data, to estimate carbon stocks in plant biomass and soils across Canada,” says Gonsamo.

Researchers say this emphasizes Canada’s global responsibility to climate change since the findings reveal a quarter of the world’s soil carbon stock is found in Canada.

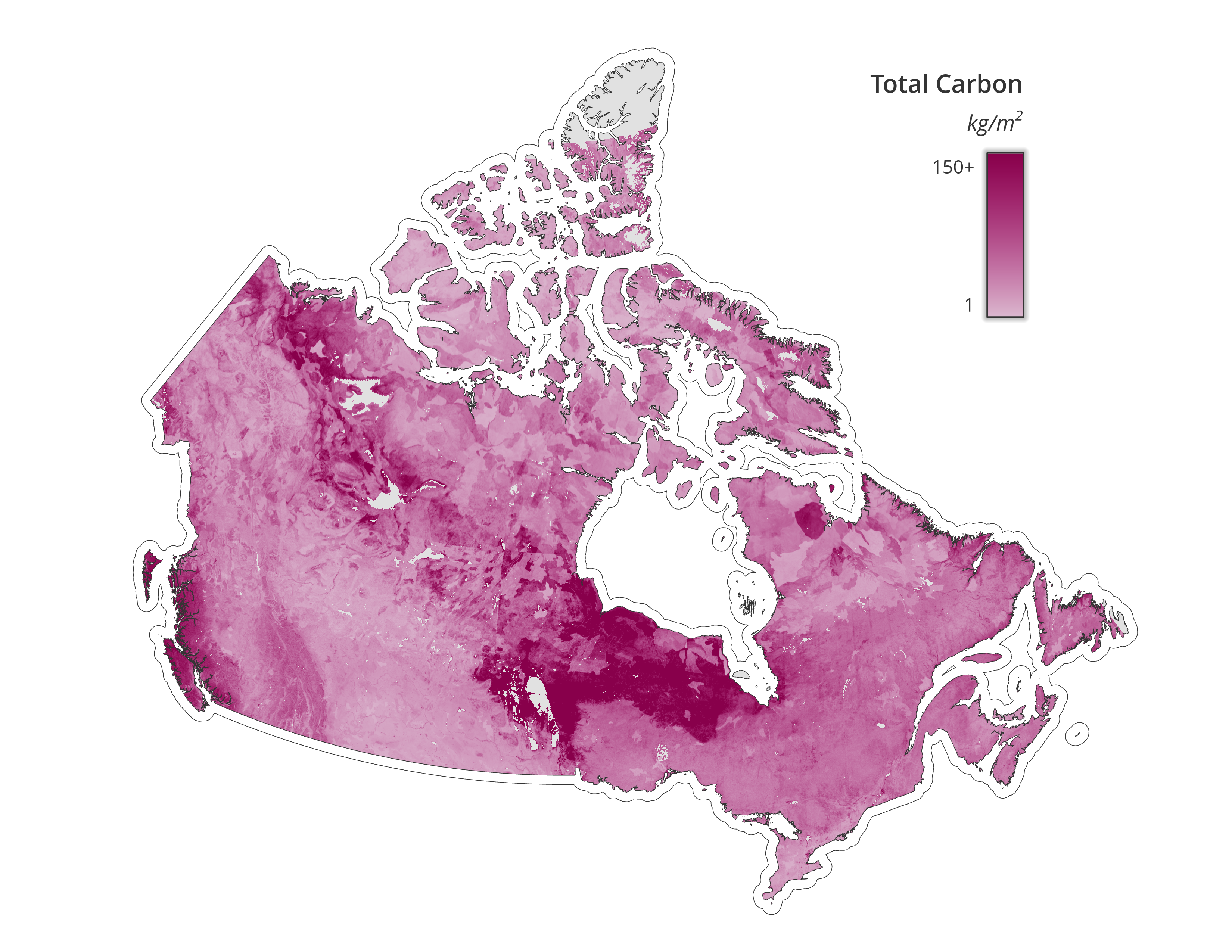

The highest density carbon-rich areas were found in the old-growth forests of coastal British Columbia, large areas of boreal forest, and the peatlands in the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands.

A map showing the highest density carbon-rich areas in Canada. (Image courtesy WWF-Canada)

“Knowing where carbon is stored in Canada allows us to strategically protect and manage the right places to prevent billions of tonnes of carbon from being released into the atmosphere,” says Megan Leslie, president and CEO of WWF-Canada. “Protecting these areas will also benefit wildlife by safeguarding habitat for important species at risk.”

One of the actions recommended by the study is to create a Carbon Guardians program to support interested Indigenous communities in monitoring and measuring ecosystem carbon on their lands.

“The Hudson and James Bay Lowlands are covered by peatlands which are an incredibly dense and globally significant carbon storage area,” says Vern Cheechoo, director of lands and resources at the Mushkegowuk Council, which represents seven First Nations in the Western James Bay and Hudson’s Bay.

“These carbon-rich areas are known as the ‘breathing lands’ to our Elders, and hold significant cultural value for the communities in the region,” says Cheechoo.

Researchers say their findings will not only help shape the country’s approach to carbon emission targets but will also help WWF-Canada in its goal to restore one million hectares of lost complex ecosystems. The findings can also help protect and steward 100 million hectares of ecologically rich habitat and reduce carbon emissions by 30 million tonnes, according to researchers.

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising