McMaster-based archive of Ojibwe writer Basil Johnston selected for cultural preservation

Published October 17, 2022 at 3:56 pm

Content note: this article refers to the former residential schools system. Information on supports is published at the end.

Basil H. Johnson spent his life sharing and sustaining Anishinaabe culture and language — and now work by archivists in Hamilton has ensured that his archives are part of the nation’s intitutional memory.

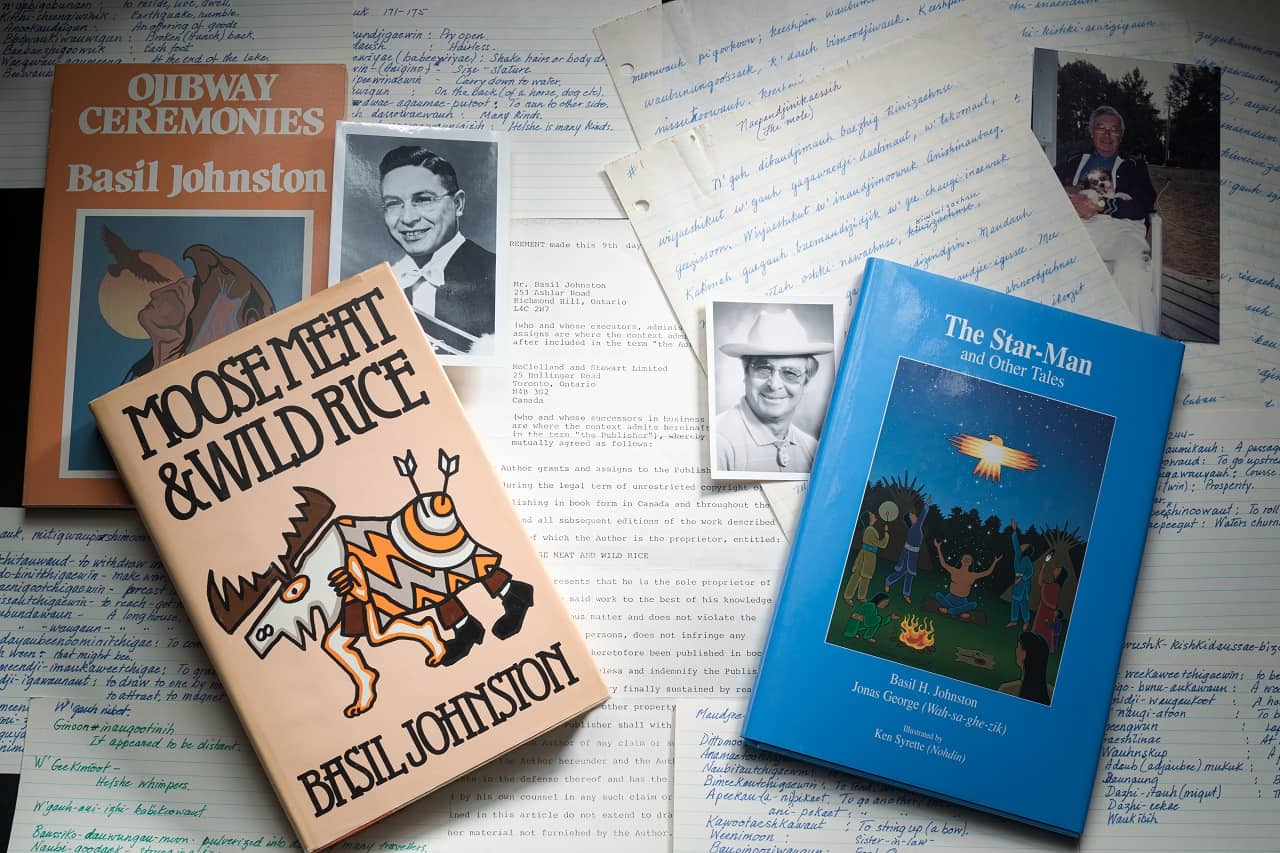

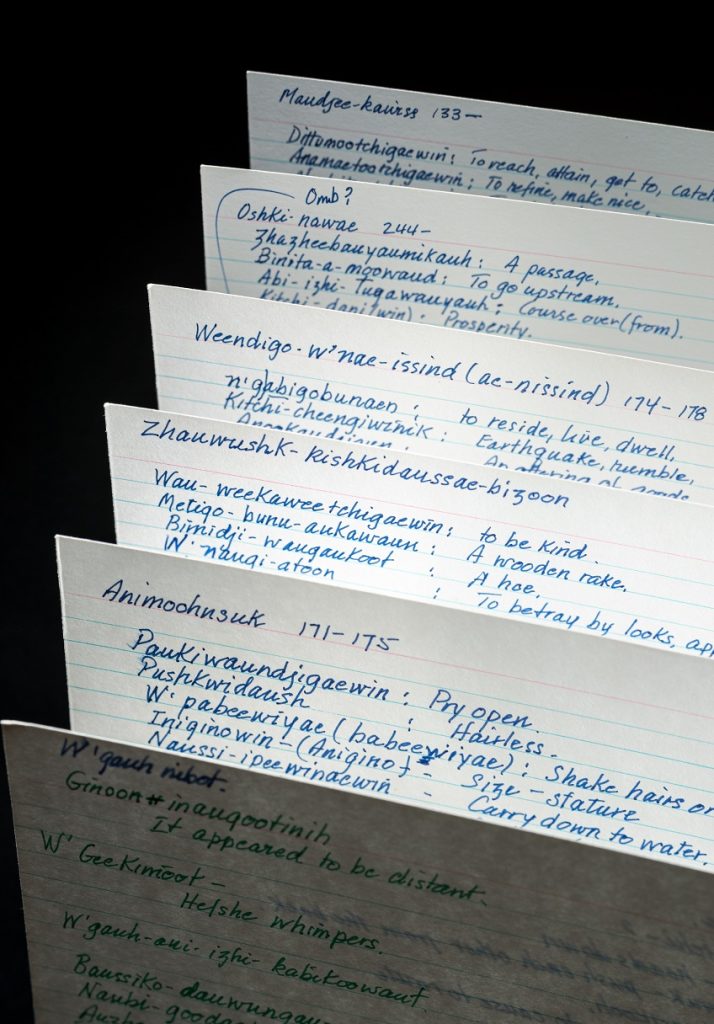

Johnston, before his energy returned to the earth in 2015, donated his papers — writings and translations, published and unpublished manuscripts, poetry, plays and prose — to McMaster University Library. The archives of the noted Ojibwe linguist, teacher, curator, ethnologist and historian also included materials related to Johnston’s experiences in the Indian Residential School System along with his research files on Indigenous land claims. These textual materials are supplemented by photographs and sound recordings, including recordings of Basil Johnston narrating traditional Ojibwe stories.

On Monday, McMaster and the Canadian Commission for UNESCO announced that the Johnston archives have been added to the Canada Memory of the World Register. The Register brings together major collections linked to the history and heritage of Canada. It complements UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme.

Johnston wrote in both English and Anishinaabemowin (also known as Ojibwa). His first book, Ojibway Heritage, was published by McClelland & Stewart when he was in his late 40s, although he faced skepticism from editors. He wrote 25 books in English and five in Anishinaabemowin. One of his short-story collections, Moose-Meat and Wild Rice, was nominated for the Stephen Leacock award for humour wrwiting.

“Basil H. Johnston was an innovator in the preservation of Anishinaabemowin,” states Cody Groat, chair of the Canadian advisory committee for Memory of the World. “He was able to convey his culture to Indigenous and non-Indigenous audiences … The Canadian Commission for UNESCO and the Memory of the World Advisory Committee are honoured to recognize the national significance of this collection that challenged the ideologies of cultural assimilation upheld by the Indian Residential School System.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which heard testimonies from some 7,000 residential school survivors, concluded in late 2015 that the system constituted cultural genocide.

Johnston was born in 1929 at what is now known as Wasauksing First Nation, of which contemporary writer Waubgeshig Rice (Legacy, Moon of the Crusted Snow) is a member. Johnston was a member of Neyaashiinigmiing, the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation.

His archives, per McMaster, pertain intimately to the places that shaped his life, especially the communities of Wasauksing and Neyaashiinigmiing where he learned the Ojibwe language and stories. His work provides a tangible chronicle of creation stories and place-names of the Anishinaabe peoples, stretching from Québec to the Great Plains.

“The addition of the Basil H. Johnston Archives to the Canada Memory of the World Register is a deserving recognition of his remarkable contributions,” states Vivian Lewis, McMaster University Librarian. “(It) also celebrates the dedication of McMaster’s archives and research collections team in ensuring archives of Indigenous Canadians are preserved and accessible to the public.”

Johnston was a high school teacher in the Toronto area in the 1960s. But he then moved to the Royal Ontario Museum as an Anishinaabemowin storyteller and teacher. He created audio programs to teach Anishinaabemowin. He wrote and recorded stories in Anishinaabe with the aim of preserving his language for future generations of speakers.

Johnston, recognized as an Elder and Knowledge Keeper within his nation and community, was involved with articulating the protocols which regulate access to the archival material. The collection will be used to support Indigenous studies at McMaster and beyond, the university says.

People who need emotional support or assistance can contact the Indian Residential School Survivors Society toll-free at 1-800-721-0066. The society also offers a 24-hour crisis line at 1-866-925-4419.

(Photos: Ron Scheffler, McMaster University Library.)

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising