Have regional governments ‘run their course?’ Oakville mayor offers his views to province

Published November 10, 2023 at 10:10 am

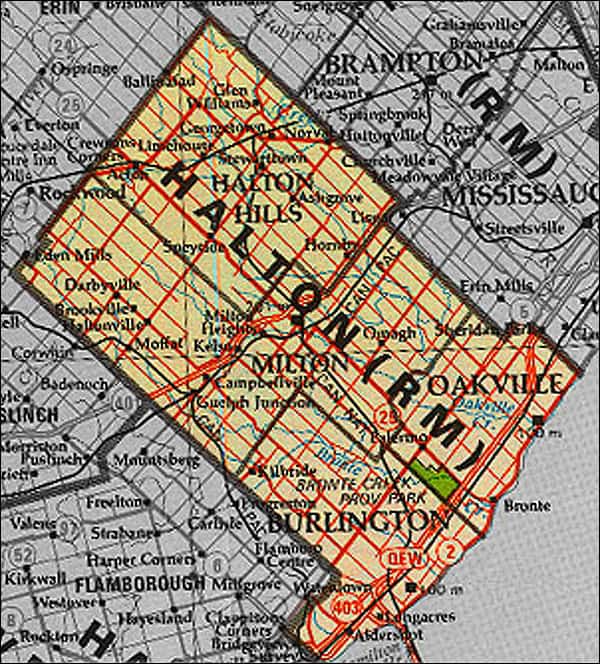

A report on the future of regional government commissioned by Oakville Mayor Rob Burton suggests regional governments “have run their course” and Halton residents may be best served if the Region was dissolved and “two strong cities” of Oakville and Burlington were created, with much of the rest of the region being awarded to Wellington County.

The report, The Introduction of Regional Government in Ontario, does not specifically mention Milton and Halton Hills, but the inference is that some or all of the lands in those communities would merge with Guelph and the other towns in Wellington.

Zachary Spicer, an Associate Professor and Head of New College School of Public Policy and Administration at York University and the author of the report, does not make the claims himself but cites the autobiography of long-time Chatham-Kent MPP and cabinet minister Darcy McKeough, who served as Minister of Municipal Affairs under Premier John Robards from 1967-71 and is considered one of the architects (along with Robards) of the regional government system.

McKeough, who is now 90, argued in his 2016 autobiography The Duke of Kent that there was little value in continuing regional government in southern Ontario as they are “far too small to” continue to provide value for residents.

“One tier,” he insisted in his book, “wherever possible” should be a general rule when addressing the evolving municipal system in southern Ontario. In Halton, specifically, he argues the region should be dissolved and “two strong cities” should stand in its place: Burlington and Oakville. Both should be expanded, he said, with the remainder going to Wellington County.

Burton provided the report Monday to the members of the provincial standing committee on heritage, infrastructure and cultural policy, which is meeting at Queen’s Park regarding the future of regional government.

Former Housing and Municipal Affairs Minister Steve Clark announced last November that would appoint facilitators to ‘review’ regional governments in Halton, York, Niagara, Durham Simcoe and Waterloo, while declaring that Peel Region would be dissolved by 2025.

When Clark resigned amid the Greenbelt scandal, Paul Callandra took over the portfolio and said the standing committee would look at the issue instead.

“On Monday, I provided information to the committee that is reviewing regional governance,” Burton said on Twitter. “Former Minister McKeough said municipalities should not be frozen in time. We should always be innovating and improving the way we organize to deliver services to our residents.”

Spicer digs into the history of regional governments in his report, noting that the traditional way of thinking in Ontario was to separate urban and rural municipalities as both areas had different cultures and economies, with rural inhabitants viewing urban areas with “suspicion” because it “challenged” the ordered nature of rural living.

Rural inhabitants viewed urban areas with suspicion, with historian Rosemary Sweet summing up the separation in her 1999 book The English Town, stating that “the dirt, the filth and physical corruption of urban streets were repeatedly employed as a metaphor for the immorality and spiritual corruption which urban living engendered among its inhabitants.”

These views originally stemmed from the ways that cities were presented as centres of evil and vice in biblical works, such as Sodom and Gomorrah or Babylon in the Old Testament, Sweet noted. Rural residents, she contested, were seen as more hard working and honest, taking simple pleasure in their agrarian lifestyle, and “rarely deviating into vice.”

That rather utopian and class-driven philosophy, which could be argued is still relevant in today’s politics, became outdated post-war, Spicer declared, especially in urban areas like Toronto, which was the first to be regionalized with the creation of Metropolitan Toronto in 1953.

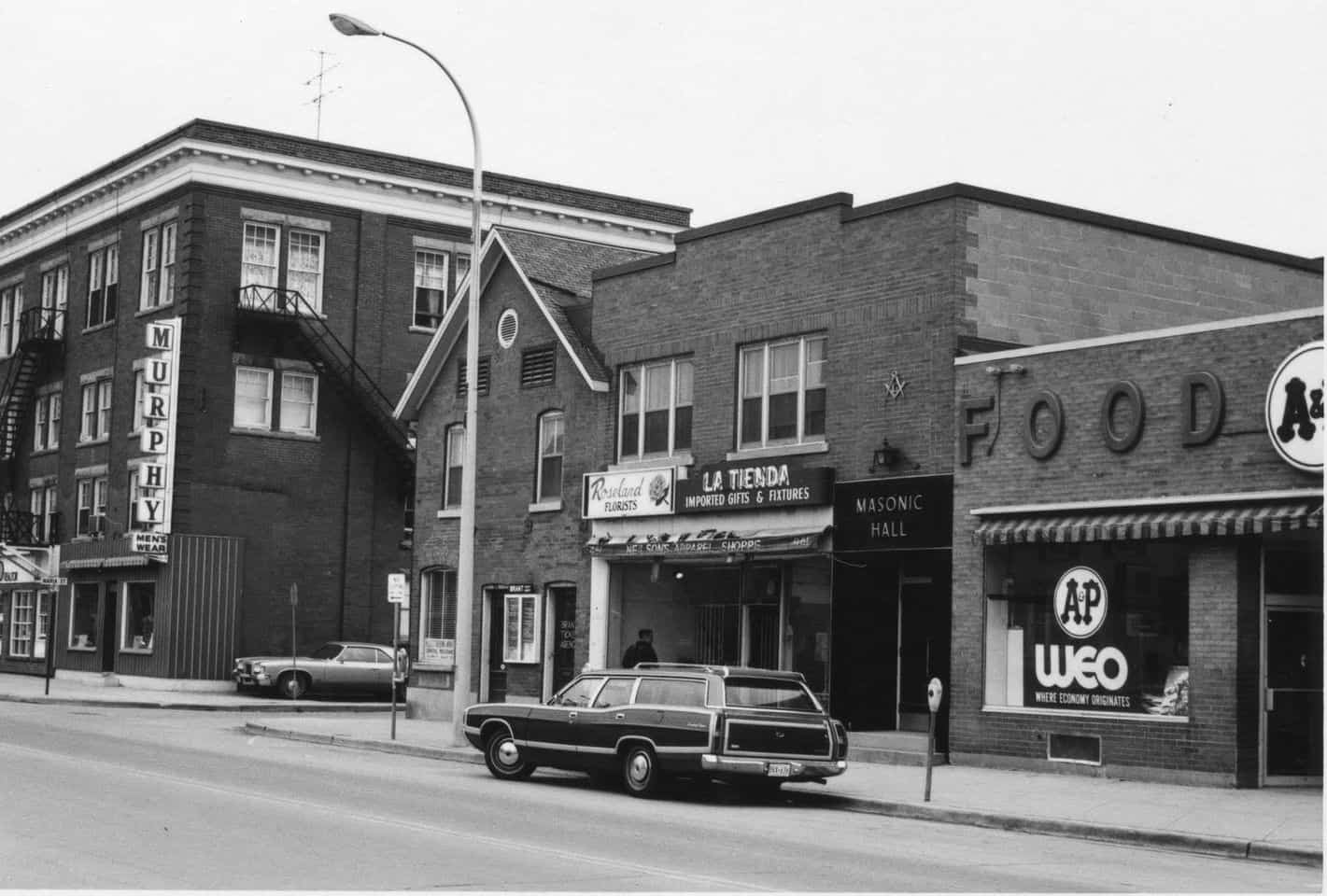

Burlington in 1973

With old notions that urban growth should be contained within a central city surrounded by rural hinterland no longer a reality in Toronto, the Province soon realized that the same urbanizing pressures were “reverberating throughout much of southern Ontario.”

Metropolitan Toronto was established as a unique entity, with two key financial distinctions from traditional county governments, Spicer said in his report: it was able to assess real estate for taxation purposes and it was allowed to issue debentures on behalf of itself and all local governments within its territory.

But widespread suburbanization was occurring around other major urban centres in Ontario, such as Hamilton, Oshawa, Barrie, Newmarket and Brampton, with the increase in automobile sales – especially in key auto manufacturing centres like Oakville and Oshawa – a key factor in promoting suburban expansion and outward migration from urban centres.

Several key reports were also important in bringing regional government to other pockets of the population. The first was the 1965 report of the Select Committee on the Municipal Act and Related Acts, which found that Ontario’s rapid urbanization required larger municipal units. The second, Spicer discovered, was the report of the Ontario Committee on Taxation, which suggested a tiered system of regional government for the province with varying service and policy responsibility was the way to go.

Beginning with the Ottawa area, a series of local reviews took place with the creation of 10 regional governments as the eventual outcome: Ottawa-Carleton (1969), Niagara and York (1970), Halton, Peel, Hamilton-Wentworth, Waterloo, Sudbury and Durham (1973) and Haldimand-Norfolk (1974).

In his book McKeough argued that he “was not fomenting revolution so much as devolution.” The point, he maintained, was to give local communities the institutional tools to manage rapid growth, stating during a 1969 speech to the Ontario Association of Rural Municipalities that a municipal structure “created for a horse-and-buggy society was hopelessly inadequate for this age of space travel.”

Rationalization, modernization and “bringing prosperity” and “a fairer delivery of services” to municipalities was at the heart of this process,” he added.

With the regional government structure created to be able to evolve over time McKeough did not see much value in continuing regional government in much of southern Ontario. Instead, Spicer said the long-time cabinet minister (McKeough also served under Bill Davis) believed that “larger and more flexible upper-tier institutions should be in place” to capture much of the GTA.

McKeough and his boss at the time, Robards (who died in 1982), built a system of local government that was designed to meet a specific challenge – rapid urbanization. In doing so, Spicer declared, they were willing to abandon generations of institutional thinking and formally link urban and rural governments together to better manage growth and extend the benefits of urban life to rural communities.

Robarts and McKeough, Spicer contended in his report, both left the door open to further change, arguing that the government’s policies were intended to be “flexible in its provisions” and responsive to changing circumstances. “We must accept the need for constant review and for revisions when conditions warrant,” McKeough said.

Robards is no longer around to lend his views but McKeough, Spicer argues, “clearly feels that such institutions have run their course.”

inhalton's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising