Guaranteed income talks ramp up after report from parliamentary budget officer

Published April 8, 2021 at 2:26 pm

The guaranteed income drum has been beaten by this reporter for nearly a year.

It could lift millions of Canadians out of poverty and boost the economy.

It’s been tested, studied, and analyzed by experts in several different fields.

Not only does the data show that a guaranteed income could boost the economy and improve or replace our buggy and sometimes inadequate social programs and safety nets, but a guaranteed income could also improve our overall health, reduce crime, and alleviate pressure on our social and emergency services altogether.

In short: a guaranteed income has shown to improve the overall quality of life of its participants while providing an economic boost.

And before the “guaranteed income is communism!” crowd shows up, I’ll point out that the concept has received support from the voices of capitalism.

Under the model that was piloted in Hamilton, Brantford, Thunder Bay, and Lindsay people would receive a benefit to bring their income about three-quarters of the way up to the poverty line, with payments rolled back by 50 cents for every dollar earned above that level.

That would amount to a $17,000 yearly benefit for a single person or $24,000 for a couple.

So if an individual earned $34,000 or more in a year, they would lose your guaranteed income. Consider it a top-up for those living below the poverty line.

The Ontario experiment, which federal officials monitored closely, was ended early with a change in government from Liberal to Conservative.

A concept that appeared to be on life support has been revived, though.

The parliamentary budget officer released a report Wednesday (Apr. 7) that suggests a universal basic income could cut poverty rates in Canada by almost half in one year.

The report landed just one day before the opening of a three-day virtual Liberal convention, where Liberal MPs and grassroots party members from east to west are pushing the idea in top priority policy resolutions.

The price tag is hefty and it would have to be viewed as a long-term investment.

It’s estimated by budget officer Yves Giroux to cost $85-billion in 2021-22, rising to $93 billion in 2025-26. Many believe that will reinforce Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s view that now is not the time to embark on a costly new program.

Giroux concluded that the federal government could almost halve poverty rates if it launched a basic income program similar to one previously studied in Ontario.

Driving his work were questions from parliamentarians about the effects of a basic income program, which has picked up political traction over the last year as the COVID-19 pandemic put the economy into a tailspin. At its worst, the pandemic cost the country about three million jobs and reduced hours and incomes for 2.5 million more.

The grassroots of both the Liberal and New Democratic parties have put forward resolutions at their respective policy conventions this weekend to make a basic income a core policy.

For the most part, Giroux estimated a basic income would increase disposable income for those at the bottom of the income scale by 17.5 per cent, or just over $4,500, while those higher up the earnings scale would see their incomes drop slightly.

The reason for the drop would be another caveat in the modelling, that the federal government would remove refundable and non-refundable tax credits aimed at fighting poverty.

Overall, Giroux’s report said more than 6.4 million people would see their disposable income rise as a result of a basic income program, on average by 49.6 per cent, while 16.8 million more would have their net income fall by 5.4 per cent.

Giroux’s report also said that the interaction between tax rates, elimination of credits and earnings as part of basic income would make some workers rethink taking on additional employment hours if it meant losing income through a combination of paying more taxes and receiving fewer benefit dollars.

He estimated that overall, employees would reduce their hours worked by 1.3 per cent nationally, which would cost federal coffers between $3 billion and $3.3 billion annually over a five-year stretch due to lost revenues.

—with files from Jordan Press and Joan Bryden, The Canadian Press; first published April 7, 2021.

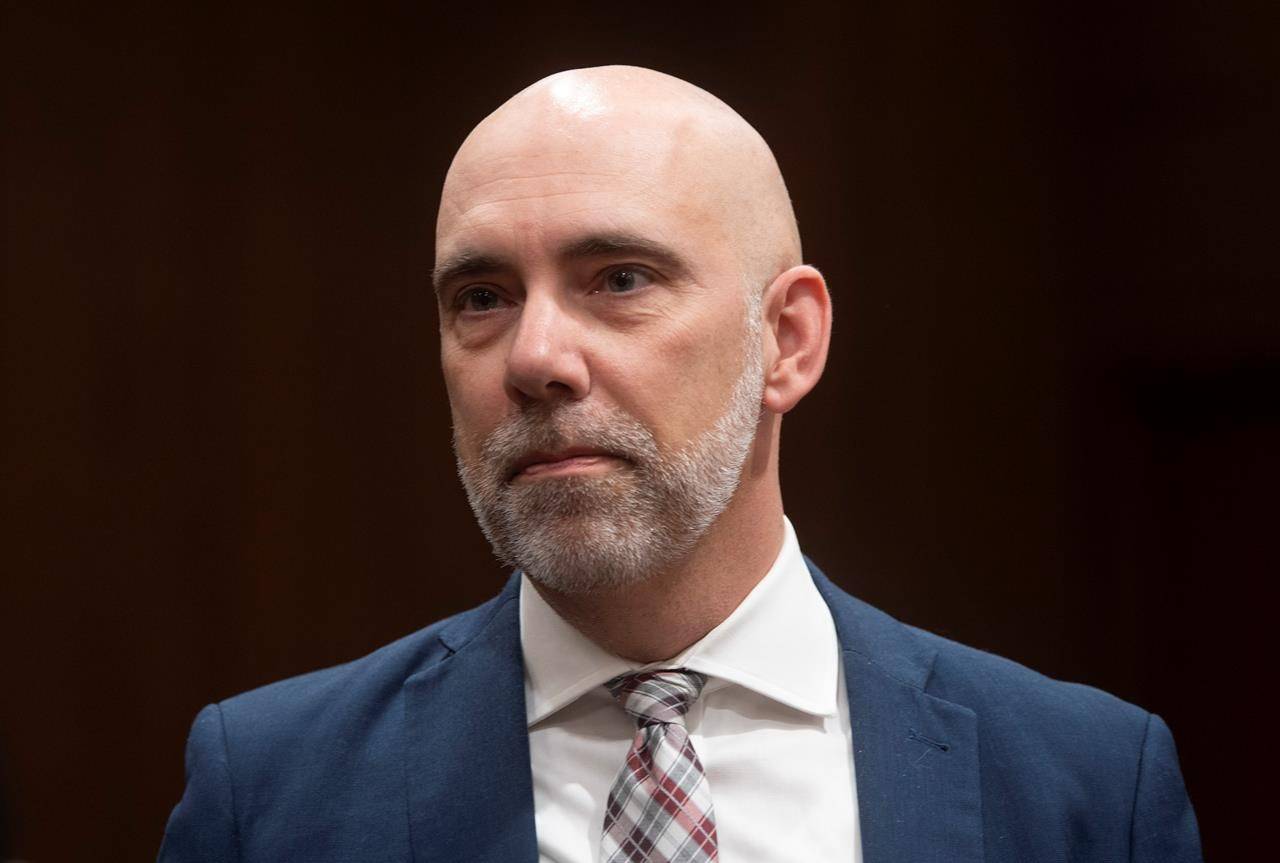

Photo caption: Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux waits to appear before the Commons Finance committee on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Tuesday March 10, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising