Food bank use on the rise in Mississauga

Published November 5, 2019 at 3:29 am

With the cost of living–and the cost of housing in particular–climbing in Mississauga, more and more residents are relying on The Mississauga Food Bank to provide them with meals.

Recently, the Daily Bread Food Bank, North York Harvest Food Bank and The Mississauga Food Bank released the annual Who’s Hungry report, which profiles poverty and food insecurity in Toronto and Mississauga.

The report reveals that 1 in 7 households in the region is food insecure and that food bank use in the area is growing at double the rate of the population, with a 4 per cent increase in the last year.

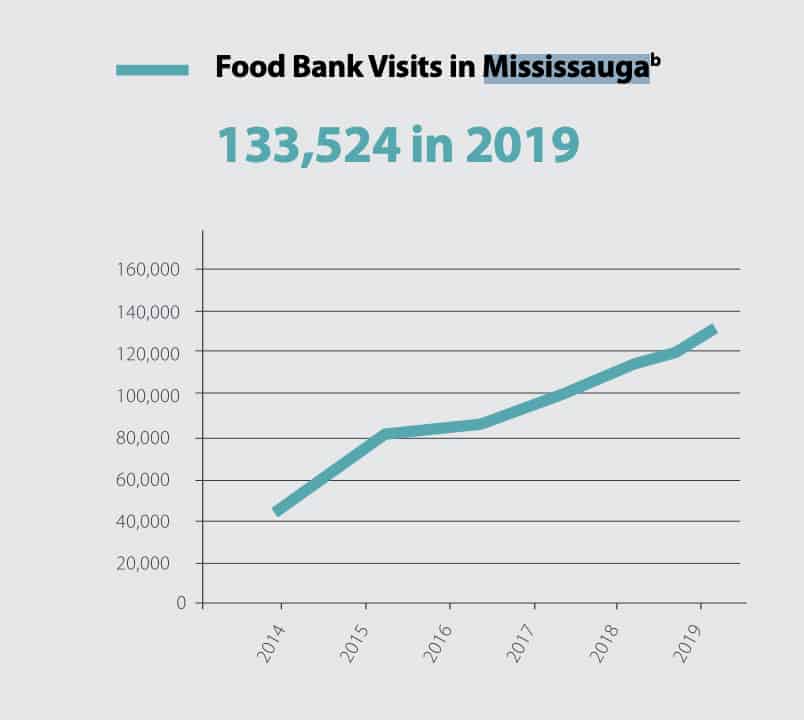

According to a Mississauga Food Bank report, in 2018, more people than ever turned to the food bank to help them provide their families with healthy, nutritious food — a 13 per cent increase over the previous year.

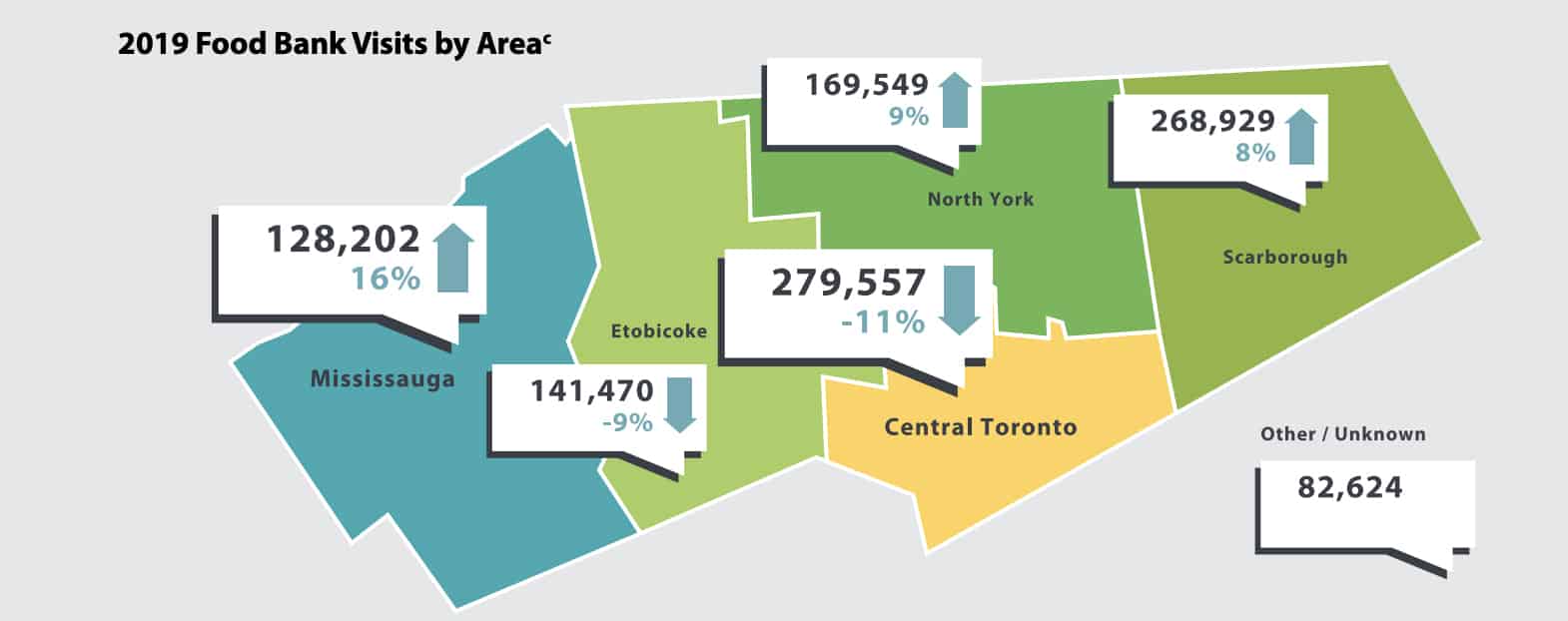

The report says that there were over 1 million food bank client visits in the Toronto region this past year and that 98 per cent of families who responded to the survey of food bank clients are living below Canada’s official poverty line.

In the Toronto area, a family of two adults and two children is considered living below the poverty line if they have an income of $41,362 or less.

According to the document, food bank clients report spending 74 per cent of their income on housing (an increase of 6 per cent since last year), putting them at an extremely high risk of homelessness.

In Mississauga, the housing situation has become increasingly more dire.

According to the Toronto Real Estate Board, the average house price in Mississauga (all home types combined) sits at $763,451.

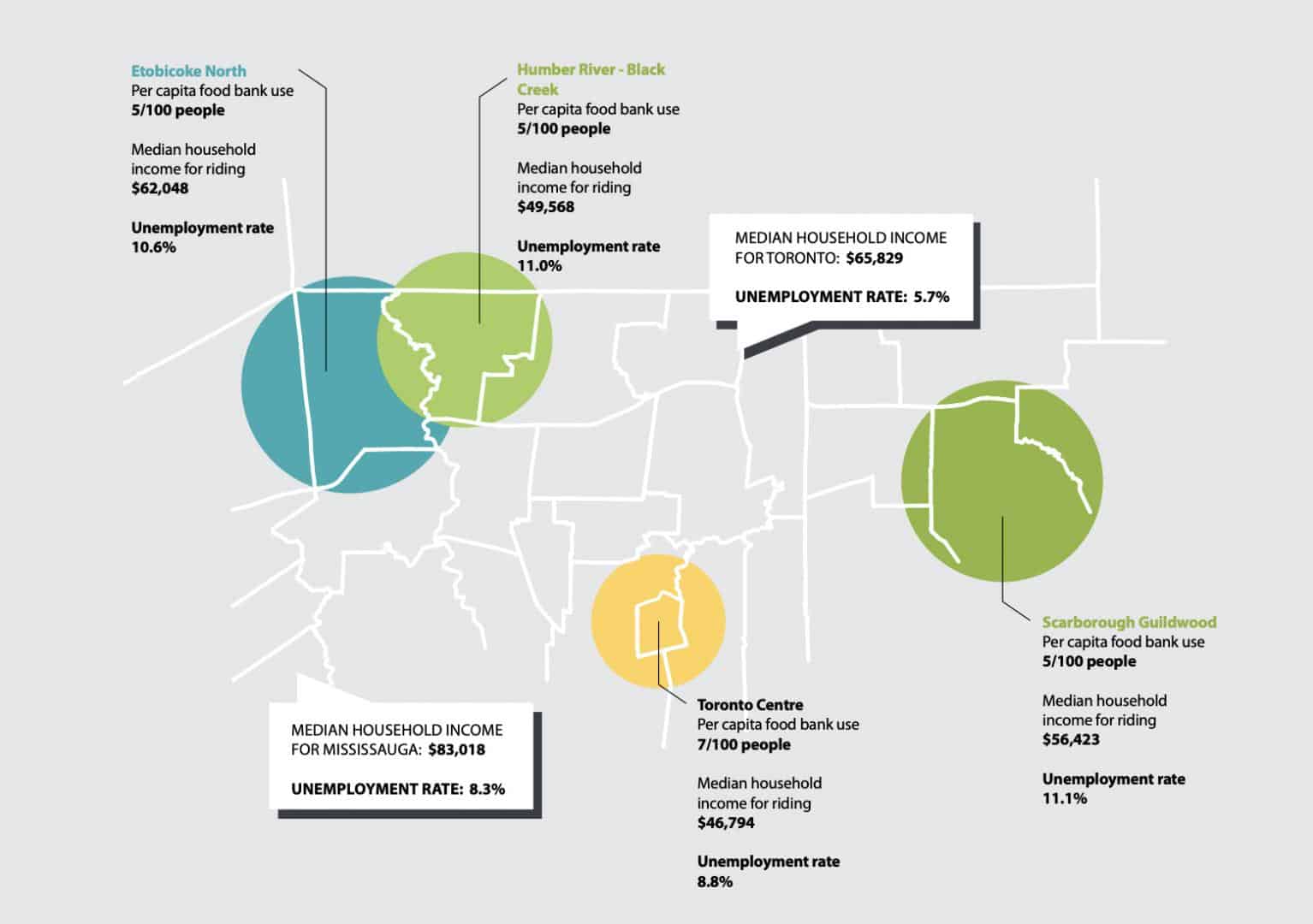

According to real estate website and brokerage Zoocasa, a household in Mississauga that makes a median income of $83,018 would not be able to purchase median-priced real estate of any kind without having to save for years to amass the necessary down payment funds.

Tenants don’t have it much better. According to a recent rentals.ca report, the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom home in Mississauga in September was $1,907, placing the city in sixth place on a list of 34 Canadian cities. The municipality finished seventh for average monthly rent for a two-bedroom at $2,301.

Because housing has become incredibly costly, the median amount of money left for food and all other expenses after rent is paid is $7.83 per person, per day. According to the Who’s Hungry report, that amount has declined by 3 per cent since last year.

The report contains other disturbing numbers, pointing out that 52 per cent of food bank clients have skipped a meal to pay a bill. Twenty-five per cent of parents reported that their children go hungry at least once a month.

Hunger also disproportionately affects people of colour.

According to the report, 25 per cent of food bank clients identify as Black, compared to only 8 per cent of the Toronto population.

The report also shows that the greatest proportion of food bank clients are working-age adults between 19-44 years of age, living in single households.

The report says this can be attributed to a lack of programs and supports tailored to single adults, causing this portion of the population to fall through the cracks.

“In the past year, there has been a significant increase in food bank use in Mississauga. This alarming trend is shared with other food banks across the Toronto Region, meaning more of our neighbours are struggling to access healthy, nutritious food,” says Meghan Nicholls, executive director, The Mississauga Food Bank.

“Who’s Hungry makes it clear more action must be taken to realize each Canadian’s Right to Food in their community.”

In 2018, the Mississauga Food Bank provided 19,525 clients with assistance and support. Local food banks in the city gave out seven or more days worth of healthy groceries on 134,364 visits, and hungry children received 11,411 meals.

While the stats are alarming–and are probably unlikely to improve significantly until affordable housing and poverty reduction plans start producing tangible results in Toronto and Mississauga–a Mississauga food bank report suggests the community has come together to support its more vulnerable neighbours.

The report says that community donations allowed local food banks to distribute 2,236,468 pounds of food across the city. In fact, the report says that community members donated food valued at almost $5 million.

The report also says that almost half of the food that was distributed last year was fresh and frozen food items like meat, milk, fruits, and vegetables–an 102 per cent increase over the amount of fresh and frozen food distributed the year before.

The Mississauga Food Bank also launched ReclaimFRESH; a new food rescue program that will partner with local grocery stores to prevent edible, healthy food from being thrown away prematurely.

“In the next four years, we estimate the program will help source food for over 5 million meals for your hungry neighbours,” the report reads.

As far as solutions are concerned, the City of Mississauga is working to reduce poverty through its Making Room for the Middle housing plan, which aims to incentivize developers to create units that middle-class households (such as those who make between $50,000 and $100,000) can afford.

The plan also includes a new bylaw that mandates that developers replace any rental stock that they demolish in an effort to keep the city’s fairly precious supply of rental stock intact (as of now, the city boasts a low 0.9 per cent rental vacancy rate).

Last year, the Region of Peel–which is comprised of Brampton, Mississauga and Caledon–launched the 10-year 2018- 2028 Peel Poverty Reduction Strategy, which aims to mitigate and reduce the impact of poverty by tackling income security, economic opportunity and well-being and social inclusion.

The Who’s Hungry report also says the federal government, which recently introduced Canada’s first official poverty line in 2018, has set targets to reduce poverty to 20 per cent below 2015 rates by 2020, and by 50 per cent by 2030 through the Poverty Reduction Act.

There are some challenges when it comes to combatting poverty, however.

The report notes that since many of its clients use social assistance programs, changes to Ontario Works (OW) and the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) are cause for concern.

In 2018, the provincial government cancelled the Basic Income Pilot Project which provided a steady income to over 4,000 participants.

The report points out that, instead, the government embarked on a social assistance review and announced a number of reforms to OW and ODSP. While the report says the province has promised some positive changes, such as providing enhanced employment services and training, a commitment to providing wraparound supports, and a simplified rate structure, it finds other reforms “deeply concerning.”

The report says the scheduled 3 per cent increase to social assistance rates was cut to 1.5 per cent and a proposal was made to change the ODSP eligibility criteria to use a more restrictive definition of disability that excludes those with episodic conditions.

The transitional child benefit that provides $230 per child for families that are ineligible or awaiting the Ontario Child Benefit and Canada Child Benefit was cancelled and the percentage of social assistance benefits clawed back when a recipient has part-time employment earnings was increased from 50 per cent to 75 per cent.

Fortunately, the province made some changes in the face of criticism.

“Food banks across Ontario advocated against these changes, and in October 2019, the government announced that they would not be moving forward with eliminating the transitional child benefit or the proposed changes to employment earning clawbacks,” the report reads.

“At this time, the government announced that they would be focusing on a broader plan to improve social assistance and employment supports. We applaud the government for cancelling these changes, and we will look for further opportunities to collaborate with the government to strengthen social assistance service delivery.”

The report also said the cancellation of the minimum wage hike has caused concern, along with the removal of the two paid personal emergency days formally granted to all workers in the province.

“Given the rise of temporary and part-time labour, we were particularly concerned to see the repeal of provisions that required employers to pay employees equal wages for the same work, regardless of whether they were casual, temporary, or part-time,” the report reads.

On the upside, the food banks are encouraged by moves to increase affordable housing at the federal level.

“One of the most promising elements of the national housing strategy released in 2019 is the Canada Housing Benefit, which provides funding directly to individuals and families living in subsidized or private market rentals but struggling to make ends meet,” the report reads.

The report notes that the federal government is in the process of negotiating the implementation of this benefit with provinces and it is expected to be rolled out in 2020.

Some of the federal investments under the national housing strategy require cost-matching from provincial governments and, in 2019, the government of Ontario re-affirmed its commitment to matching these funds, the report says.

As a result, Ontario will receive $4.2 billion of funding for the housing sector over nine years to repair and expand social housing and implement the housing benefit.

To help resolve food security issues, the report recommends that all levels of government adopt a rights-based approach to decision making to ensure that policies help to advance the right to food and promote equity, strengthen social assistance, support low-income households by expanding tax benefits and creating pathways out of poverty, invest in affordable housing and tenant protections, enhance access to affordable childcare, and ensure access to affordable, nutritious, culturally appropriate food in each community in the Toronto region.

The Who’s Hungry report provides quantitative and qualitative data about the experience of hunger and poverty in the Toronto region.

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising