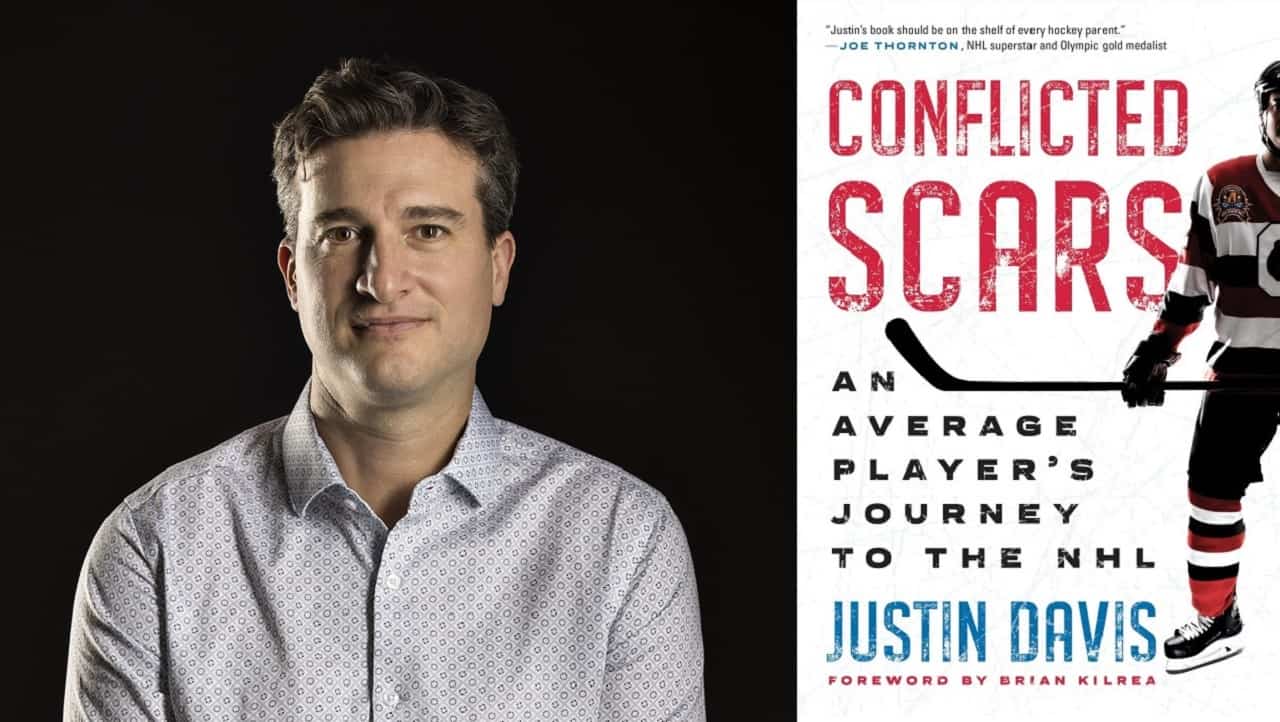

‘Conflicted Scars’; OHL alumnus with Hamilton, Halton ties writes about hockey culture

Published October 19, 2022 at 4:34 pm

Justin Davis wanted his children to know why their dad is the way he is, and ended speaking his truth to the adults in the hockey dressing rooms.

The former pro hockey winger who grew up in the Hamilton-area community of Carlisle has written a memoir, Conflicted Scars: An Average Player’s Journey To The NHL, which was published this week by ECW Press. Davis began putting his days climbing the hockey ladder to the page in 2019 when he was off work from his high-school teaching job while facing health challenges that stem from his playing days. Since then, as anyone who keeps up with the news knows, Hockey Canada and Canadian Hockey League have been engulfed in a series of sexual-abuse scandals.

“What happened was that I was on short-term disability, I was having some back issues and I was bedridden for about a month,” says Davis, 44, who played for three Ontario league (OHL) teams in the 1990s and also helped the Dundas Real McCoys win the Allan Cup, the national senior title, in his victory lap as a player in 2014.

“I was having some post-concussion issues. I read the book Game Changer by Ken Dryden. It is about a guy I played against, (the late NHL defenceman) Steve Montador, and I saw a little bit of myself in him. As I was reading the book, I saw the effect that hockey had on him. I thought, ‘you know what? I’m going to write a memoir to my kids.’ I was just going to tell them all the good things that happened and all the great stories.

“It was supposed to be a 10-, 15-page memoir to my kids that maybe they’d read in 15 years, and it spiralled,” adds Davis, a Guelph resident and father of three who teaches physical education at Orangeville District Secondary School. “I’d be telling a good story and then I’d remember something else. I’d be telling a story about Kingston (his first OHL team) and the hazing stuff, concussion mistreatment, came up. So it just sort of evolved.”

‘What you described happened to me’

The structure of the ladder to the big league, the NHL, requires children leaving home to play the highest level of competition possible for their age. The rewards are evident. The average NHL salary is US$3.5 milllion. And alumni of the OHL, a pro-format league whose players are mostly 16 to 19 years old, score 25 to 30 per cent goals in NHL games on most given nights.

Boys carry the immense risks. Davis, whose prose tells of struggles with mental health and depression following a series of brain injuries, and of team hazing activities, says his prose has hit home with OHL alumni of his era.

“I had two guys reach out the other night that I played with in two different places and they said, ‘Thank you for telling these stories,’ ” Davis says. ” ‘What you described happened to me, word for word, the next year, and happened to someone else the next year… It is nice to have fellow former players reach out and reassure me that, number one, this happened, and number two, it happened to others.

“They’re happy that they can talk,” he adds “There are a lot of guys who are living their lives. They haven’t told their wives what happened. They’re sharing, and for mental health, that’s fantastic.”

Concussion mistreated

Davis, who was a Washington Capitals draft choice, estimates he had 12 to 15 brain injuries (commonly called “concussions”) during his playing days. He says “you almost feel guilty” about being public about playing hurt. Davis adds he is receiving great treatment these days from SHIFT Concussion Management in Guelph.

He had a brain bleed at age 18 after he was blindsided during an OHL game in Plymouth, Mich., in 1997. Team management with the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds desired to wait until they returned to Ontario to take him to a hospital. Davis needed three days of intensive care in a U.S. hospital. The Sault Ste. Marie team later tried to get Davis’s parents to pay the $15,000 U.S. hospital bill until his adviser, Allan Walsh, got involved.

“I recall telling the GM the medical bills resulted from a hockey related injury and there was no real dispute whether the club would be paying the outstanding bills,” says Walsh, who is now one of the top agents in the NHL. “And they ultimately paid.”

Brain injury risks that hockey and football players in North America face have been known for almost a century, according to TSN investigative reporter Rick Westhead’s 2020 book Finding Murph. The brain of the aforementioned Montador was found to be ravaged by CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) after his death in 2015.

The first case of CTE in a former NHLer was confirmed in 2009, when the brain of the late Reg Fleming was examined. The late Canadian sports journalist Earl McRae wrote in the mid-1970s that Fleming clearly had cognitive issues that stemmed from taking repeated blows to the head in the pre-helmet days, similar to those diagnosed in many boxers.

More recently, the NFL faced a player-safety scandal when Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa suffered brain injuries during two games in a span of five days.

For Davis, that reaffirmed that he was on the right track to write candidly about his challenges. On the TV screen, he saw Tagovailoa exhibit the same symptoms that he did a quarter-century ago that night in Michigan.

“He had the fencing syndrome, where your fingers are all frozen,” Davis says. “That’s what happened to me in the Soo (playing for the Greyhounds). It just makes me sick to my stomach when I see that he did not get the proper care.

“You need that, especially in junior hockey… You just need the right people in place to protect you from yourself. We all want to go out and play, but you need the right person in place to stop you from going back out. I thought I was invincible, and now I’m 44 and getting treatment every day, and battling through some things. The CTE, it scares you, when you read about the impacts. The reality of life is sinking in a little bit.”

The CHL, which includes the OHL, Québec and Western leagues, has stepped up its game somewhat with player supports. The OHL levies more severe in-game penalties and supplemental discipline for blows to the head and can suspend players who have three fighting majors in a season. Payout of education packages that players receive if they move on to U Sports hockey is centralized at the league level. It also increased mental health supports after 20-year-old Terry Trafford died by suicide in March 2014.

Times and sensitivities change, but CHL players are still the same age.

“The biggest takeaway (from the book) for adults is they are the ones expected to protect kids,” Walsh says. “They are the ones entrusted with the health, welfare and safety of young hockey players. It’s a sacred trust and too often, that trust has been broken by the ‘adults in the room.’ If we are truly changing the culture, that must come first from leadership, whether we’re talking about Hockey Canada, the OHL or minor hockey programs.

“What Justin has done in telling his story, his thoughtful self=reflection with honesty and transparency from the heart has the ability to impact many people’s lives,” he adds.

‘Things that you are taught are normal actually are abnormal’

Hockey Hall of Fame coach Brian Kilrea, whom Davis won the Memorial Cup with in 1999 with the Ottawa 67’s, wrote the foreword. Future hall of fame forward Joe Thornton (Davis’s teammate in Sault Ste. Marie) and two of Canada’s most respected sports hosts, TSN’s James Duthie and Sportsnet’s Ken Reid, contributed jacket blurbs.

Conflicted Stars covers Davis’s hockey arc from his formative years, which included youth hockey in Flamborough and with the Halton Hurricanes AAA program. He won three major Canadian championships, all on overtime goals. Davis had the primary assist on Matt Zultek’s ’99 Memorial Cup-winning for Ottawa and was central to the Western Mustangs winning the University Cup in 2003. The Allan Cup in ’14 with Dundas completed a unique trophy hat trick.

“With hockey culture, you move away when you are 14, 15, 16 — the team becomes your family, the coaches are your parents,” Davis says. “And that leads to how you think, and how you act, when a lot of these people aren’t great role models. That is when the things that you are taught are normal actually are abnormal. As a teacher, I know that those are the years where you are impressionable.”

For every traumatic experience Davis has worked through, Conflicted Scars includes numerous relatable stories about his days in the OHL, Ontario University Athletics and German pro leagues. Kilrea and Western coach Clarke Singer stand out as mentors who made it fun to go to the rink.

Davis and his wife, Jessie Davis, have three children, Josh, Grace, and Avery, ages 16 through 12. Justin Davis, coaches high-school hockey and volunteers with the OHL’s a player mentorship and chaplain position, and keeps ties to Hamilton as a 20-year Tiger-Cats season-ticket holder.

“I’m not angry at hockey,” he says. “I just want to help fix things in any small way I can.”

(Editor’s note: inthehammer was provided with a digital advance reading copy of Conflicted Scars, which the author read in its entirety five days before conducting interviews. Cover photo: Heather Pollack, ECW Press.)

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising