Chief of the Mississaugas of the Credit says co-operation needed to achieve reconciliation

Published June 14, 2021 at 8:24 pm

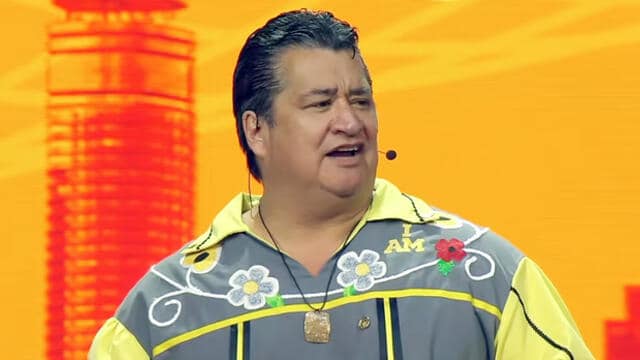

After a lifetime of dealing with failed promises from the federal government regarding inadequate housing, lack of clean water and a plethora of social issues, you can forgive Stacey Laforme, Chief of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, if he has a built up a bit of frustration over that time.

And considering the inequities facing Indigenous people across this country, from the fact they make up 30 per cent of the prison population and 22 per cent of the victims of violent crimes – despite making up less than five per cent of the population – to the disproportionate numbers of First Nations people facing poverty and joblessness, you can forgive him if he feels a bit of resentment as well.

And if we’re talking about the overt and systematic racism that has never truly gone away in the 500 years since European settlers arrived on these shores, not to mention the genocidal legacy that was the Residential School System, then you could also make a case for him to be angry at the cards he has been dealt by Canadian society.

But Chief Laforme knows anger is not the way to move forward.

Anger was certainly one of the emotions he felt when the 215 unknown and unnamed Indigenous children were discovered on the grounds of the Kamloops Residential School a few weeks ago – “grief, sadness and a little bit of anger” was how he described it at the time – but he knows that in order to change the narrative, co-operation is what is required, not anger.

“There was a lot of anger in the moment. Everybody was in pain,” Laforme recalled when the Kamloops story broke. “But we need to see the big picture and you can’t if you’re angry all the time. What we needed to show is our love, but that was hard. There were some very angry people out here, and rightfully so.”

It’s not just First Nations people who were angry, Laforme said, citing the recent beheading of the Edgerton Ryerson statue outside the Toronto university that carries his name. “In the moment, a lot of people needed to see it come down.” He wouldn’t have called for such action, he added, but he wasn’t unhappy either. “They’re down now,” he shrugged.

Reconciliation is a long way away, he added, but it has to start today, and Laforme is encouraged by the outpouring of support his band and First Nations people all over Canada have received since the Kamloops story broke nearly three weeks ago.

People have reached out asking how they can participate in ceremonies honouring the missing children, and while Laforme appreciated the sentiment he said the way you grieve is not important; only that it has meaning for you.

“Do it your own way and we’ll do it together.”

What has also been encouraging for the Chief has been the level of support from Canadians.

“We’ve been able to stand together on this,” he said. “Because these children are children of Canada. Not just Indigenous children.”

The next step, he said, will be to make sure the story remains top of mind among all Canadians.

“We’re not going to let this be forgotten,” he said. “This is a moment in the history of Canada, and we don’t have many moments like this to lose. From climate change to racism, the issues we’ve been facing for a long time are still going on.”

“The only way to do better is to recognize the connections we have as people – as human beings – and then recognize the connections we all have to the world around us.”

Chief Laforme said First Nations people will need all the support they can get from Canadians in their fight to get more funding – needs-based funding – from the federal government to reduce the inequities native bands face every day.

Laforme remembers the Stephen Harper days as being particularly difficult for Indigenous people – “his apology meant nothing to me because it was just lip service” – but it hasn’t gotten much better under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

He admitted he has seen some progress within his own band under a Liberal government – a water main project built in 2019 has finally brought clean water to the Mississaugas of the Credit and to the nearby Six Nations Reserve – but Trudeau’s promises for real change have been nothing more than words so far.

“He’s made a lot of grandiose statements,” Laforme said. “But don’t just show me ideas; show me the plan. Show me an implementation strategy. That’s the only way we can hold the government accountable.”

One thing Laforme is sure of is that the federal government will pay for the ground testing of the other residential schools in the country. There has been a groundswell of voices demanding the government use their own resources to use ground-penetrating radar on the rest of the schools, including the infamous ‘Mush Hole,’ the Mohawk Institute in nearby Brantford that operated from 1831 to 1970.

“I am confident they will pay for that,” he said.

He is also confident that more bodies will be found as the work progresses.

“This is not the last time we’re going to find this at residential schools. We’re going to find more, and there will be more pain.”

But Ottawa has still not committed to equal funding for First Nations schools or any need-based funding model, something Laforme believes is crucial in helping native bands escape the cycle of poverty, chronic unemployment and inadequate housing that is with them every day.

“We want funding to pay for what we actually need because there are so many gaps in the system,” he said. “When it comes to clean water, housing and education, we want our children to be equal with the rest of Canada.”

With a federal election looming in two years (or earlier), Laforme is doubtful Canada will see any change in the “dynamics” of government, but that doesn’t mean he will be giving up advocating for change.

“We’ll meet with them – whoever they may be – and we’ll try once again to hold them accountable. We just need to make sure they make some commitments to First Nations people so we can get to work.”

This also where the rest of Canada can step up and help, Laforme said.

“Our numbers are not large enough to change an election. Let’s try and correct some of the wrongs of the past because if everyone comes together, we can get this fixed.”

When the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced on May 27 the bodies of 215 Indigenous children – some as young as three – had been discovered on the grounds of the Kamloops Residential School, the first emotion Chief Stacey Laforme and the rest of the residents of the Mississaugas of the Credit reserve felt was profound grief. That was followed by sadness, and as Laforme described it, “a little bit of anger.” And it was with those feelings fresh on his mind when Laforme, a noted poet and storyteller, put pen to paper and wrote this poem.

Reconciliation

I hear crying. I don’t know why.

I didn’t know the children. I didn’t know the parents. But I knew their spirit. I knew their love. I know their loss. I know their potential.

And I am overwhelmed by the pain and the hurt, the pain of their families and friends. The pain of an entire people unable to protect them, to help them, to comfort them, to love them.

I didn’t know them, but the pain is so real, so personal. I feel it in my core, my head, my spirit.

I sit here crying and I am not ashamed. I will cry for them, and many others like them. I will cry for you. I will cry for me. I will cry for what could have been.

And then I will calm myself, smudge myself, offer prayers and know they’re no longer in pain. They’re at peace.

In time I will tell their story. I will educate society so the memory is not lost to the world. And when I am asked ‘what does reconciliation mean to me?’ I will say, I want their lives back. I want them to live, to soar. I want to hear their laughter, see their smiles.

Give me that and I will give you reconciliation.