Ahead of Hamilton urban boundary vote, analysts say intensification plan misses the mark

Published November 8, 2021 at 12:41 pm

Will the City of Hamilton miss the point about the missing middle?

Dr. Frank Clayton and Cheryll Case, two urban planners who InTheHammer spoke with separately ahead of a crucial vote about land use in Hamilton, said the city’s forecast of housing needs over the next 30 years does not add up.

Tuesday (Nov. 9), of course, is Decision Day, when Hamilton’s elected leadership will lock in land use till 2051. Both Case and Clayton are skeptical about the city consultants’ methodology and wonder whether it will truly address a shortage of affordable housing.

Staff recommendations to city councillors include expanding the urban boundary to allow for home construction on some 1,300 hectares of farmland, which has spurred strong community opposition and pushback from developers. The decision must be made to meet population and job growth targets that the Ford Government set out in 2020.

Hamilton has declared a climate change emergency. The city’s infrastructure deficit includes a recent water department finding that Hamilton has been losing over one-quarter of its fresh water to leaky lines.

A city’s challenge to provide city services also gets tougher when it takes up more physical space due to what is generally called sprawl.

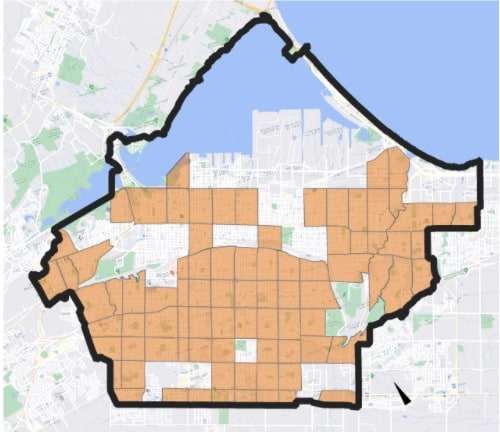

Case says the land needs assessment that will inform the city’s decision ignored yellow belt neighbourhoods. That is a term for areas where low-rise housing has been built, but more supply could be added. The assessment was performed by Lorius and Associates consultants in 2020.

“There is a demand for ground-related housing,” says Case, an author and urban planner. “There’s a belief that that supply can only be accommodated in greenfield areas or by expanding the urban boundary.

“That is not actually the case. It can also be accommodated in existing residential neighbourhoods — the yellow belt. That can include taking, for example, taking bungalows and turning them into duplexes or triplexes or semi-detached houses actually can accommodate that demand for ground-related housing.”

Filling in that so-called missing middle is seen as a way to create supply without the two extremes of highrises downtown and suburban McMansions where your house is an arm’s length from the next-door neighbours. The missing middle also helps with environmental concerns.

“It would help immensely,” Case says about the yellow belt/climate crisis tie-in. “With the climate crisis, producing additional housing supply in existing neighbourhoods allows the city to make use of existing infrastructure and also provides a population base that can help to support the improvement of infrastructure. Bus services, the walkability of local neighbourhoods, all of these things can help take cars off of the road.

“Greenfields and urban farming areas are also incredibly important for sustainability.”

Case shared a map that shows yellow belt neighbourhoods in Hamilton that could be further developed, in order to increase the affordable housing supply.

“The city hasn’t accounted for growth to happen in any of these spaces, and so that is resulting in an underprojection in a number of units that can be developed,” she says.

Clayton, who is a senior research fellow at Ryerson’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development, wrote a paper last month that critiqued Hamilton’s intensification plan.

Clayton and research assistant Lana Marcy found in their work that the proportion of new housing (known as “intensification”) that Hamilton built in “delineated built-up areas” was 35 per cent from 2008 to ’19. It has been 38 per cent since 2016.

The Lorius forecast calls for an average of 60 per cent intensification over the next 30 years — 50 for the first decade, then 60, and finally 70 by the 2040s. Clayton says doing that will require building far too many apartment towers than there is a market for in Hamilton.

“The bulk of people do want low-density housing,” Clayton said. “And if they can’t get it in Hamilton, they’ll get it in another place.

“If you want to do something about the high price of houses, the only you can do that is to increase supply,” he adds. “That doesn’t mean increase apartments if people want single-detached housing or townhouses.

“I always have this theory in my mind; that people get to their mid-30s, they settle down with a life partner, they get a kid or two and a dog, and they want to live in something close the ground. They don’t want to go down 30 flights of stairs to take the dog out.

“And if they cannot afford a detached house, they’ll go for a semi-detached, and if they cannot afford a semi-detached, then it’s a townhouse, and if it’s not a townhouse, it’s a stacked townhouse.”

Environmentalists and tenant advocates in Hamilton have also noted that living in a high-rise apartment in a city with an increasing frequency of extreme heat events also increases the potential for residents to have poorer health outcomes.

Clayton notes that the 100,000 or so immigrants who arrive in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area annually works out to a need to build 40,000 to 45,000 new homes every year. The housing tastes of newcomers, he says, usually blend with the general population.

‘Community’s wishes’

Hamilton built far more apartments than single-family homes in the second half of the 2010s, which has contributed to the city’s housing affordability crisis. Oxford Economics found this summer that Hamilton has the third-most-expensive housing market relative to income in North America.

There is a balancing act with the housing market and climate change. Case noted, though, that after the 90 per cent opposition to urban boundary expansion in a city-run survey, there was no follow-up about whether that is truly feasible.

“The city has not produced a scenario that seeks to implement the community’s wishes for zero boundary expansion,” she said.

“The exclusion of those areas which have been developed (from the land needs assessment) will lead those neighbourhoods to increasingly become unaffordable to families.”

Since growth plans are updated every five years, Hamilton is changing its forecast for the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clayton notes that COVID-19, with its attendant stay-at-home orders and social distancing, might have led to many younger adults becoming more interested in owning their own home.

“They might have changed their preference from an apartment downtown to a townhouse,” he said. “The market says what we should build. People have choices, and we can give opportunities, but we cannot dictate.”

Hamilton gained all-day GO Train service in August, but there are other cities and regions that offer shorter regional-rail rides to Toronto for would-be commuters.

“Why would you get an apartment in Hamilton when you can live in Mississauga, or Toronto, or Markham?” Clayton asks. “The (intensification plan), is out of whack, given the economic and housing market circumstances of Hamilton.”

Background

Traditionally, updating a city’s growth plan can be a mundane exercise. The Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing sets the terms.

Both parties that have governed Ontario in this century have drawn criticisms. Clayton said that the Ontario Liberal Party, which was in power from 2003 to mid-2018, took the tack that “a housing unit is a housing unit.” This might be why Hamilton saw so many more new apartments than houses over the last half-decade.

The Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario government, under Premier Doug Ford and Municipal Affairs Minister Steve Clark, have been criticized for being excessively pro-developer. The Globe & Mail reported July 15 that the province’s auditor-general is investigating the PCs’ changes to land-use planning policies.

Their report will not be released until well after Hamilton makes its decision sometime on Tuesday.

There are numerous reasons why it has come to a head in Hamilton. The city has long been an attractive market to real estate speculators. It is also falling behind on supporting equity-seeking and vulnerable populations, including the unhoused.

At this writing, the city clerk’s office has 31 delegation requests for the special meeting that is slated for 9:30 a.m. on Tuesday. It has also received more than 300 pieces of communications from residents weighing in on in the momentous decision.

Officially, it is a special general issues committee (GIC) meeting, but Mayor Fred Eisenberger and all 14 active councillors are on the GIC.

Case credits the spike in interest to a greater grasp of why ground-related housing is out of reach for so many.

“The wider public is becoming more aware of the role that urban planning has in shaping their access to affordable housing, and protection of the environment,” Case said.

“And, also, the pressures of lack of affordable housing, and the increasing need to protect our environment, are key motivating factors to why there is so much tension this time around.”

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising